I’m learning to accept the nights in which I’m trying to go to sleep and find myself involuntarily writing a blog post in my head. Like tonight. It’s 11:30 pm in a hotel in Hartford, Connecticut. Sleeping is hopeless, so I might as well get up and write.

The topic haunting me? Why we make art.

My big fat presumption here is that you, the reader, do in fact have art in mind. I must say that, given the number of photobooks produced each year with obvious artistic intentions, this presumption is true for an awful lot of photographers.

As far as the question goes—why we make art—I should tell you I don’t so much have answers as I have questions, and I’ve found some answers from other people that might help to figure this out a bit.

On the other hand, I am confident about one thing: that making art is a compulsion. We are compelled to make it. The great poet William Carlos Williams reportedly met someone at a party who said, “Oh, I would really like to write poetry, but I don’t have the time.” And he is said to have responded, “Well, you have time to shit, don’t you?”

William Carlos Williams.

A compulsion and a necessity.

When I was a book dealer in San Francisco, I worked with a book collector who had, in his youth, busked his way around Europe for a few years playing classical guitar in cafes. He told me of a woman who approached him and said, “I’ve always wanted to play the guitar,” and he replied to her, “No you haven’t. Otherwise you’d have been practicing six hours a day like me.”

A compulsion and a discipline.

Picasso. Guitar.

I was fortunate to attend the final graduation ceremony of the Hartford Art School Photography MFA under the directorship of Robert Lyons this week. After inventing and launching the program and directing it since 2010, Robert has handed the reins to the extremely capable Michael Vahrenwald and is retiring as director. One of the things Robert said to the class of 2025 in his commencement address was: don’t worry about exhibitions, don’t worry about galleries, don’t worry about publishers, just make the work.

He’s right. It’s got to be hard for these students to hear, or even harder to follow, because it bucks all self-advancement instincts. But the wise insight underlying Robert’s admonition is that once you start worrying about these indicators of “success” it can adversely affect your work. It’s so easy to gradually start to make the work you think the galleries and collectors and publishers want.

Robert Lyons.

The other wisdom is that, to achieve any of the above successes, you need a strong body of work. (And I use this term in its original sense of referring to one’s entire opus or oeuvre, not just a recent series of photographs.) Work that has an unusual vision and is bringing something different to photography. And that takes time to build, for most of us.

From all reports I’m getting, on both sides of the Atlantic, from established on up to art-star photographers, the photography market has taken a nose dive. Book sales are low. Print sales are dead. Teaching is honging in there. Galleries, if they do take on photographers, are not nurturing careers but cashing in on the self-nurtured artists with massive social followings. And while lower-paying editorial work is still available, lucrative advertising commissions have nearly vanished. Photographers everywhere are scrambling.

In a way, I wonder if we’ve slid back to the time Stephen Shore discussed recently, the very early 60s, about which he said: “My point is that photography, then, offered the enticements of neither fame nor fortune. For those of us who pursued it as an art, it was simply a ‘calling.’ I mean this literally. I felt called to it.“ (See the full quote in my blog post from July 17, 2025.) Yet we don’t even have the magazines they had back then, which gave so many art photographers a livelihood.

Stephen Shore. Photo by Sprüth Magers.

Here, copied into my notebook, is an excerpt from an article by Charlotte Cotton from 2013, celebrating the persistence of photographers who were already then finding themselves left to their own devices. She describes them as “the groundswell of pro/am photographic artists who self-publish, collectivize, and find their audiences themselves, knowing full well that the professional infrastructure for art photography is never going to accommodate them during their productive lifetimes.” Will there be exceptions to this? Yes. How many? Who knows.

Charlotte Cotton. Photo by Show Studio.

Is this a grim assessment? Or is it a liberating encouragement? Is it a resignation? Or is it the acceptance of a new reality? In Zen Buddhism, the first Noble Truth is that life is suffering. The second, that there is a way out of suffering. The third, that the way out is letting go of attachment. Atttachment was once explained by Richard Baker Roshi, in a talk I saw him give, as “wishing things weren’t the way they are.”

Richard Baker Roshi.

If this is, in fact, the new reality, it’s difficult to imagine how many photographers, who have worked really hard at growing their vision, knowledge, and skills, and who maybe even have just graduated from a grueling MFA program—how many of these people are now grieving the lost chance at what they’ve seen others achieve and what they’ve always thought was possible. And then there are the ones who’ve had it, and have felt it slip away.

During the graduating class exhibition at Hartford this week, I was talking with one of the students and his parents about career prospects going forward. We all agreed that, with an MFA, one could teach. The question the father asked was, should photography be depended on for a livelihood? I suggested that one approach was to figure out how to make a living to support the photography, and the father nodded his head emphatically in agreement. I said, support and protect the art at all costs, but don’t necessarily force the art to provide a living. The father agreed and seemed happy to find someone who felt the same way. I didn’t believe he was saying photography is secondary to career, but more that it shouldn’t be burdened with earning a living. The student was carefully digesting all of this.

So what happens when art is just art, unsupported and barely appreciated by the larger world? Is this a chance to take photography back from the marketplace? And what is art, anyway?

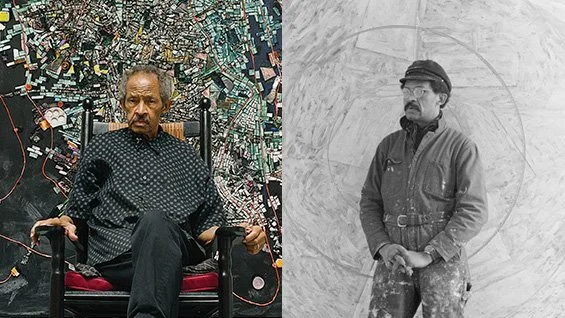

I’ve been reading the writings of the late painter Jack Whitten, whose massive retrospective just closed at MoMA this month, and whose journal was published as Notes from the Woodshed. He wrote in 1978 (his emphasis):

Painting is a gift. Please don’t ask who does the giving or what does the giving I simply do not know. From now on I will cease calling what I do experiments. The word no longer applies to what I am doing. I am the recipient of visual messages. Where these message come from, I do not know. I don’t even know what to call them. I am even confused as to their use.

Two photos of Jack Whitten.

Yes, Mr. Whitten struggled to make a living, and would have loved to sell a bunch of paintings and have galleries, which actually did happen before he died. But while he does talk about being broke in his journal, he talks so much more about his higher purpose in making art. He talks frequently about the sacred nature of this gift.

Here is a quote from the journal about the presence of spirit in art from 1976 (original punctuation retained):

One senses that he is in the presence of something. I got that from African sculpture. I have the feeling that I’m in the presence of someting and I understand that they even put certain substances into a work of art. They say that the spirit is embodied in the work. Now if it doesn’t have a spirit it doesn’t work for me….Does it have the spirit in it or does it not. If it does it works for me and it’s time to stop working on it. That’s when I send it out into the world to do its job.

So is art spiritual? Is it a calling, as Stephen Shore says?

According to the Russian film director Andrei Tarkovsky, in his book Sculpting In Time, the goal of art “is to explain to the artist himself and to those around him what man lives for, what is the meaning of his existence. To explain to people the reason for their appearance on this planet; or if not to explain, at least to pose the question.”

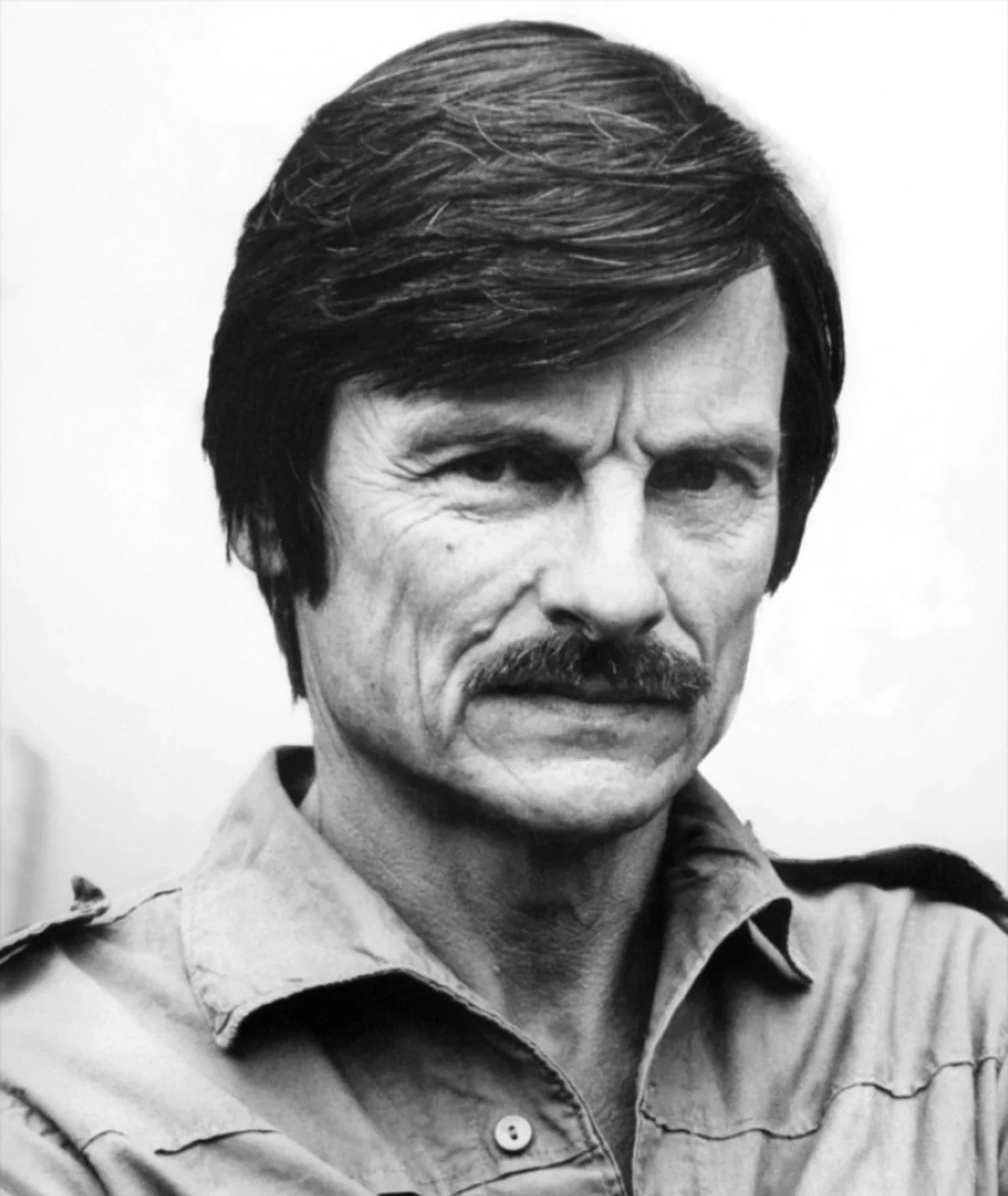

Andrei Tarkovsky.

It’s hard, watching Tarkovsky’s great movie Stalker, not to believe Tarkovsky saw art as a sacred calling, a great and selfless gift to others. (Filming the movie in the middle of a toxic waste site ended up killing him.) The main character, the Stalker, suffers deeply when his clients have no faith in what he has shown them in The Zone, an act which utterly exhausts him to the marrow of his soul. The Stalker stands for all artists.

The character referred to only as The Stalker.

Tarkovsky also writes, “Such an artist can discern the lines of the poetic design of being. He is capable of going beyond the limitations of coherant logic, and conveying the deep complexity and truth of the impalpable connections and hidden phenomena of life.”

In a similar vein, the French film director Robert Bresson said in a 1966 interview, “I firmly believe in cinema as art. Not as entertainment, but on the contrary, as a way of taking a deeper look at things, a kind of aid to man in looking deeper and discovering ourselves.”

Robert Bresson.

Are we now seeing the larger contribution of art to the world beyond the commodity it delivers? Does this role justify the artist expending more time, energy, and resources than they can ever hope to be compensated for? Has this been the role of artists since the first songs and the first marks on cave walls? And are you, as an artist, willing to continue to make art no matter the presence or absence of reward?

Like I said, I can’t answer the question of why we make art. But I’m thinking some of these comments and questions can help each one of us figure out our own answers.