I think I live for surprise.

Happy surprise, I should clarify. Not the kind I got a week ago when a young homeless man punched me in the mouth as our paths crossed. It was 10pm. I was walking my dog. Lesson learned.

No, I mean the good kind. I used to tell my advertising students at PSU (yes, I will burn in hell for that job) that they should imagine that everyone is walking along the sidewalk hoping that around the next corner they will encounter an unexpected delight. That should be your ad, I said.

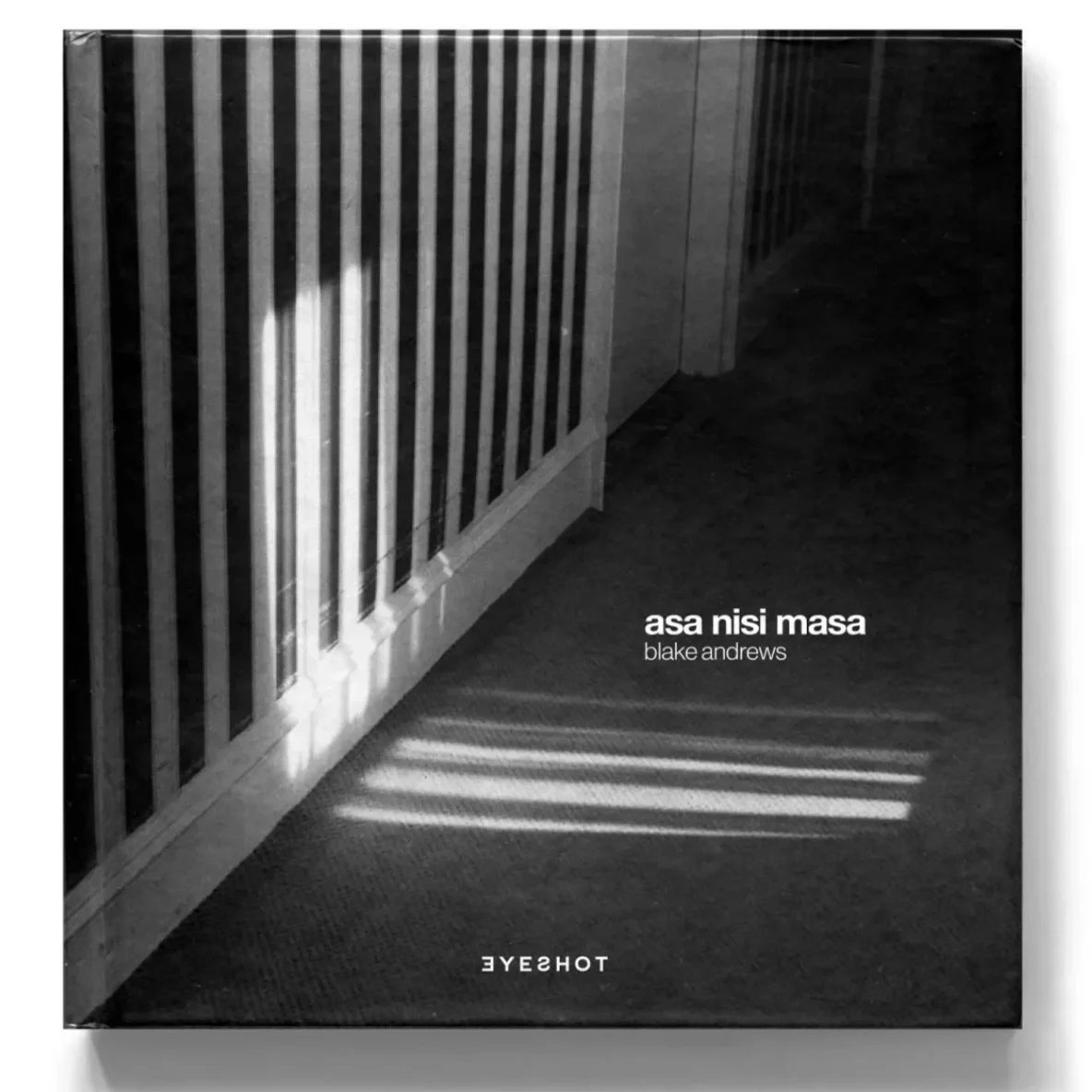

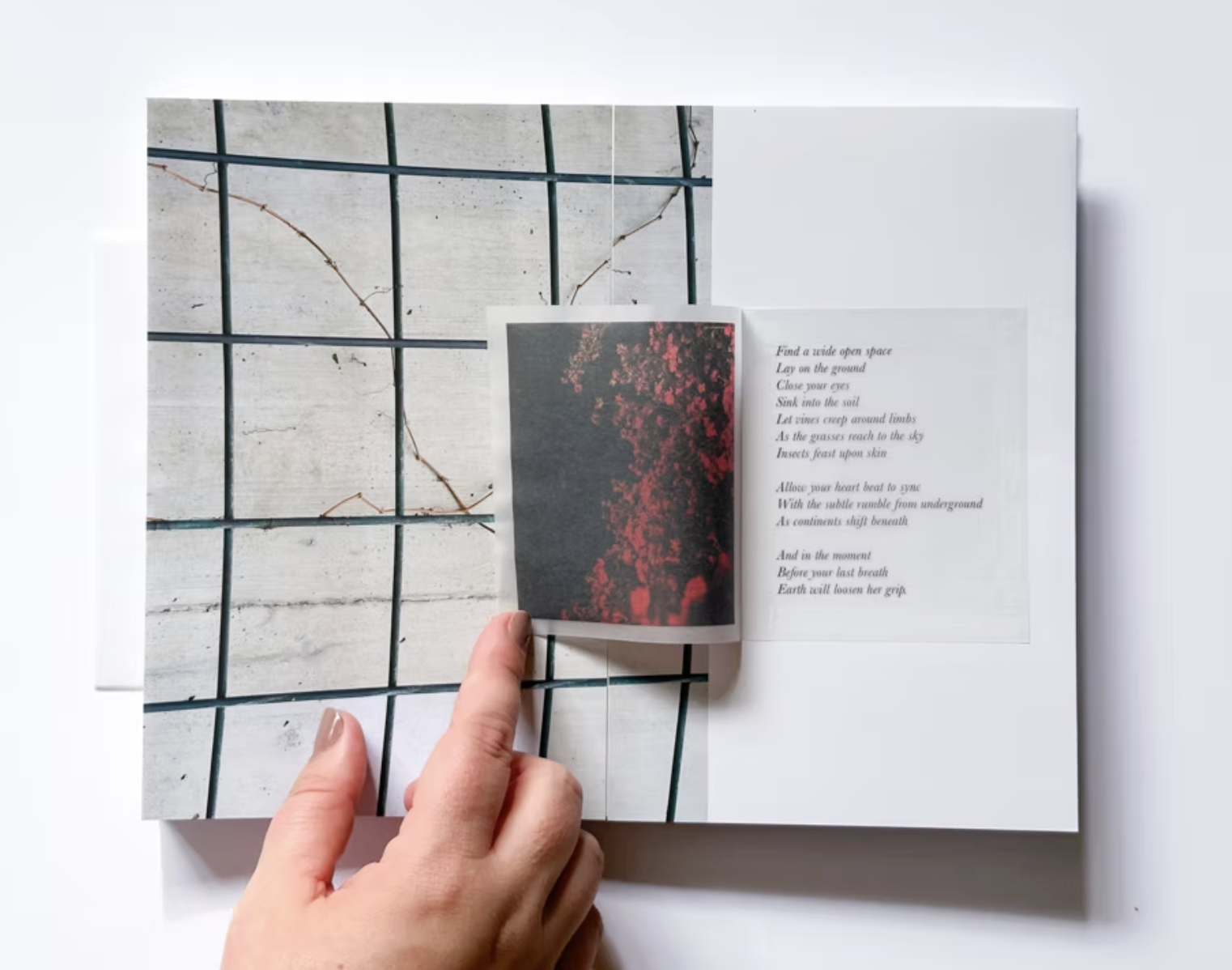

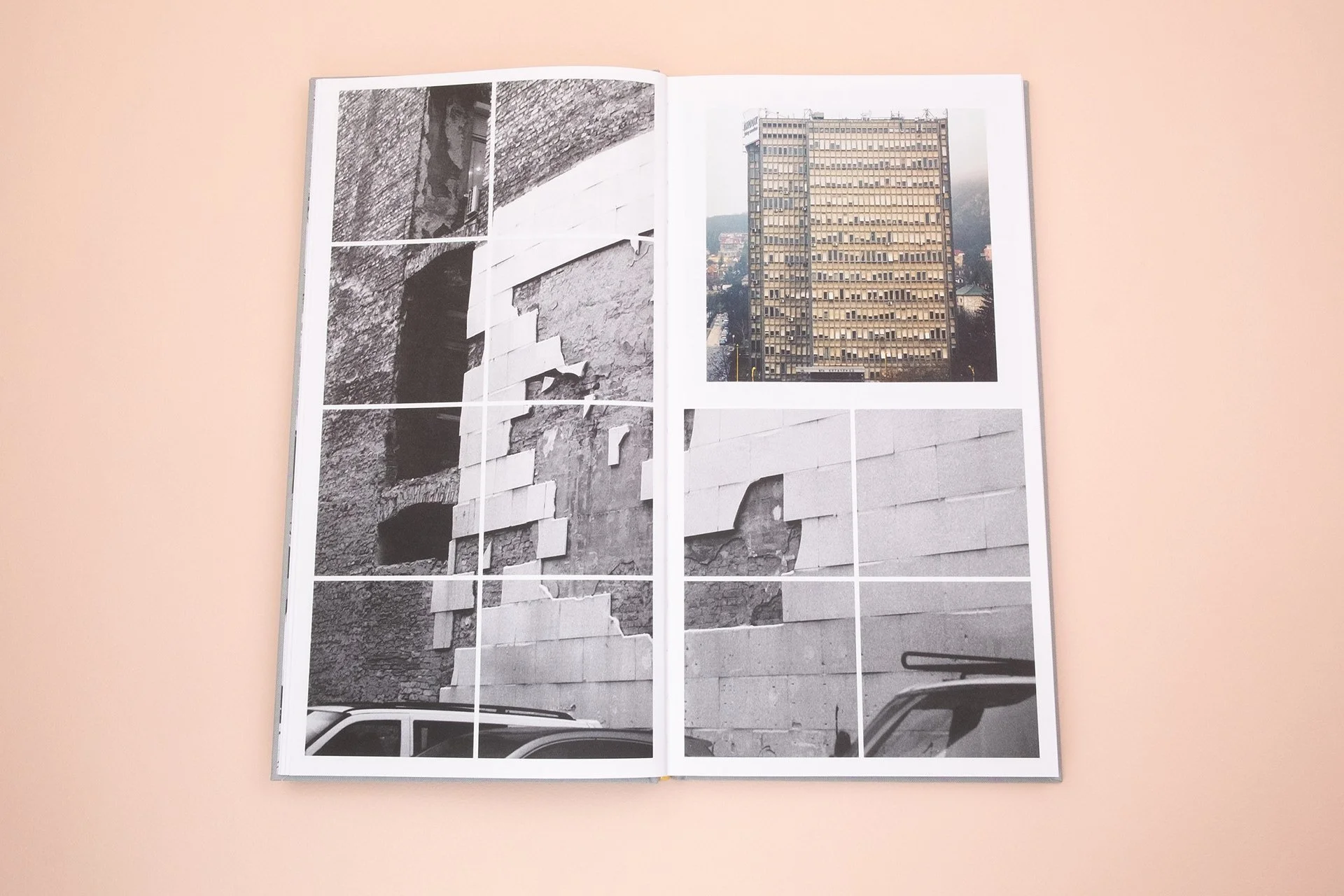

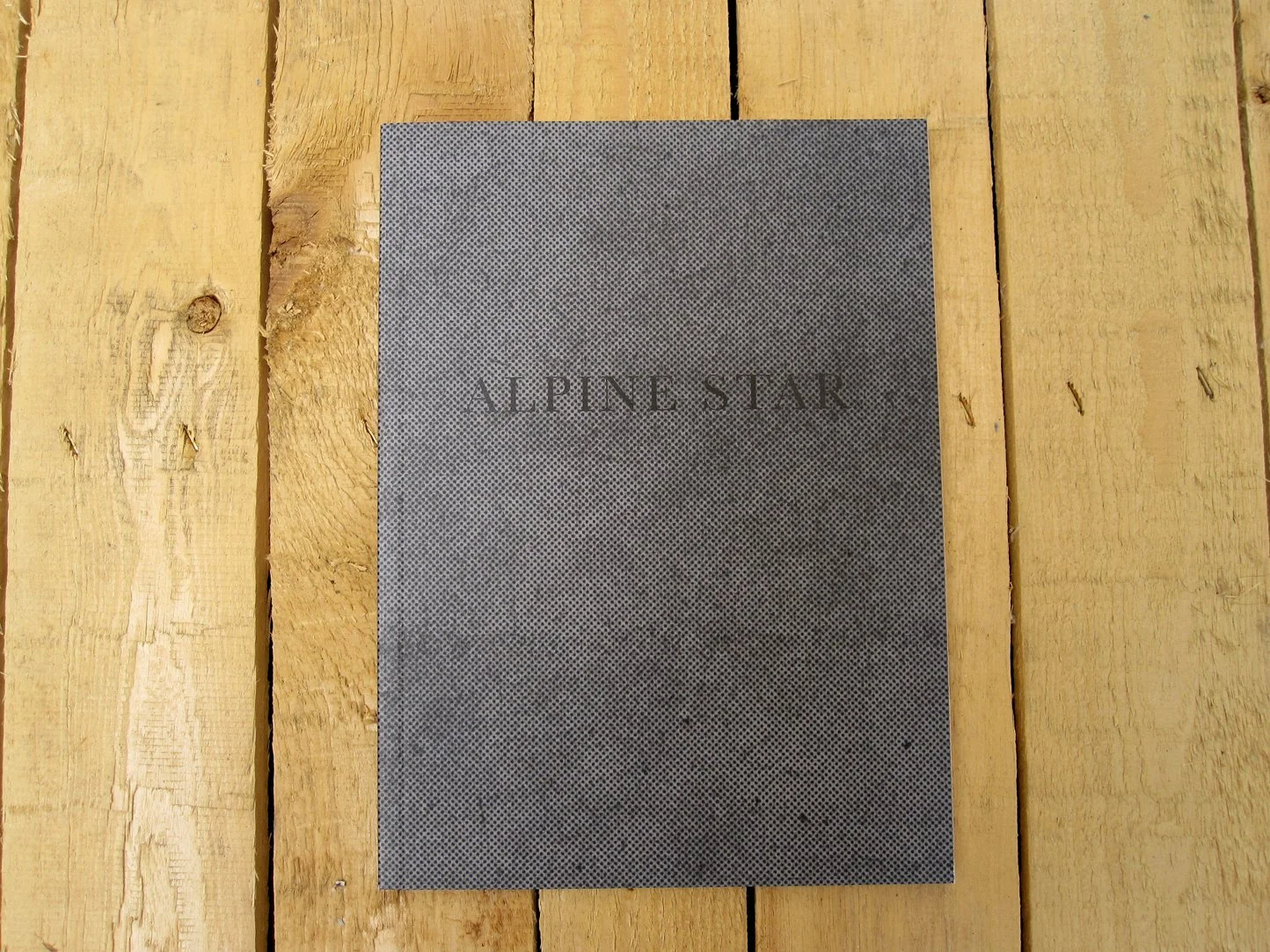

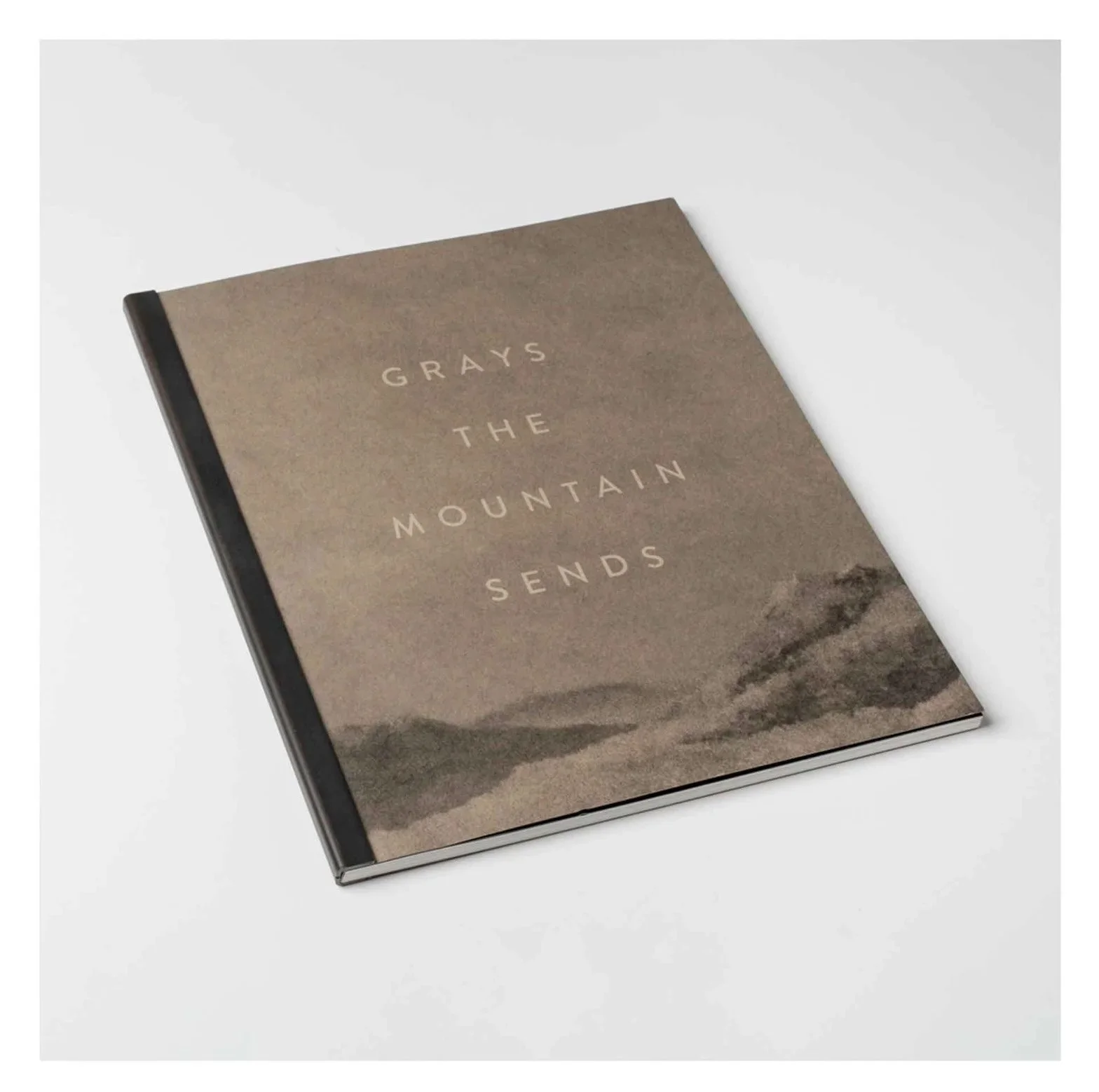

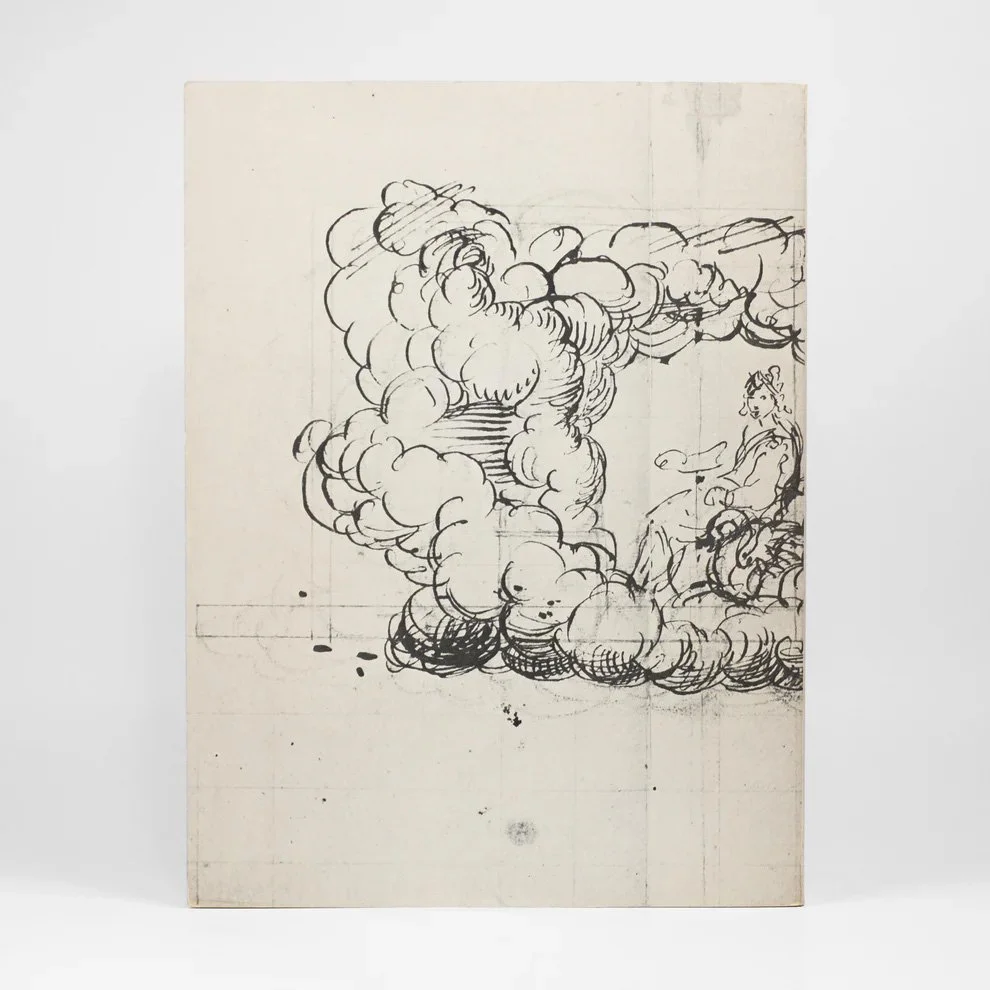

The photographs of Blake Andrews are exactly that kind of surprise. I just received his long-awaited photobook asa nisi masa, published by Eyeshot, after pre-ordering it in June. How Blake and his editor got the selection down to 123 photographs I’ll never know. Blake is a relentless shooter and, as he notes in the CV/Bio on page six, has processed 700,000 negatives to date.

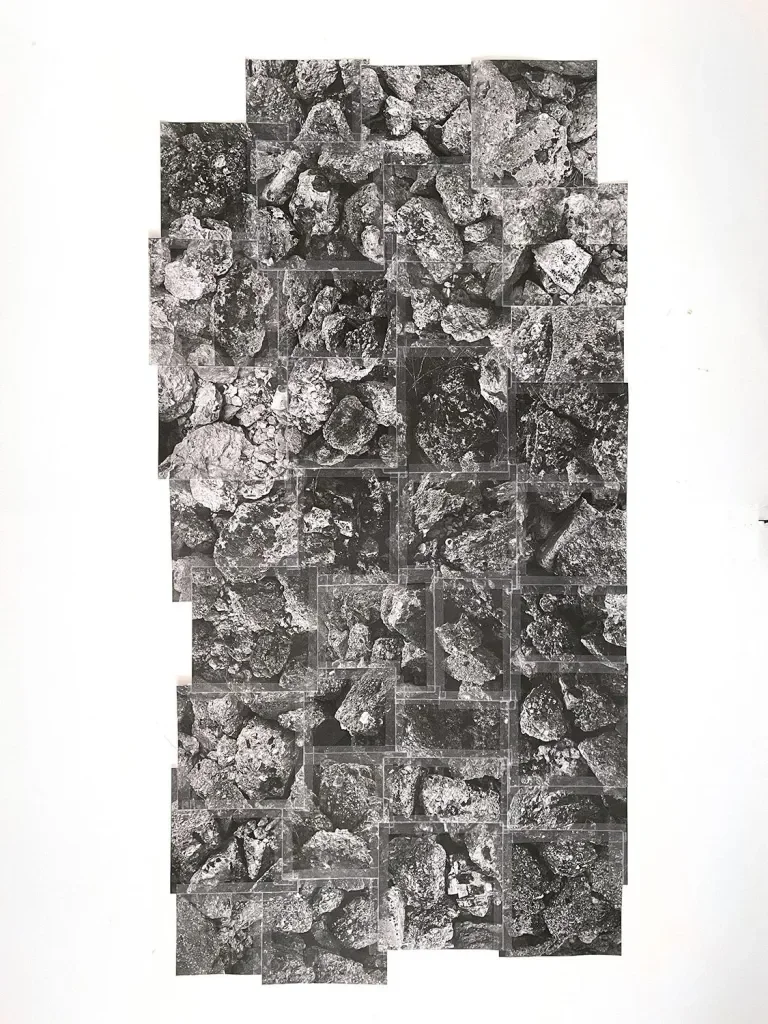

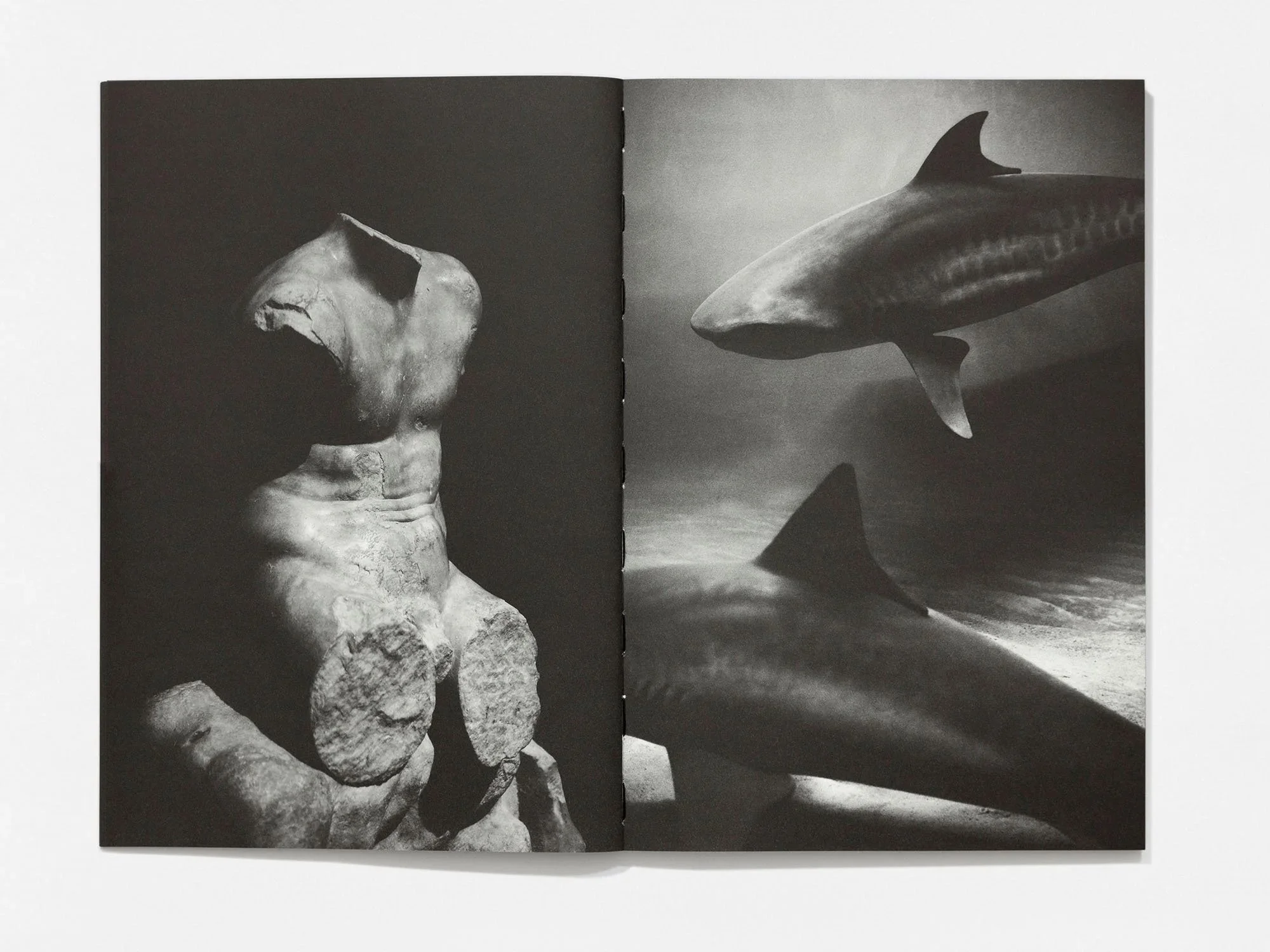

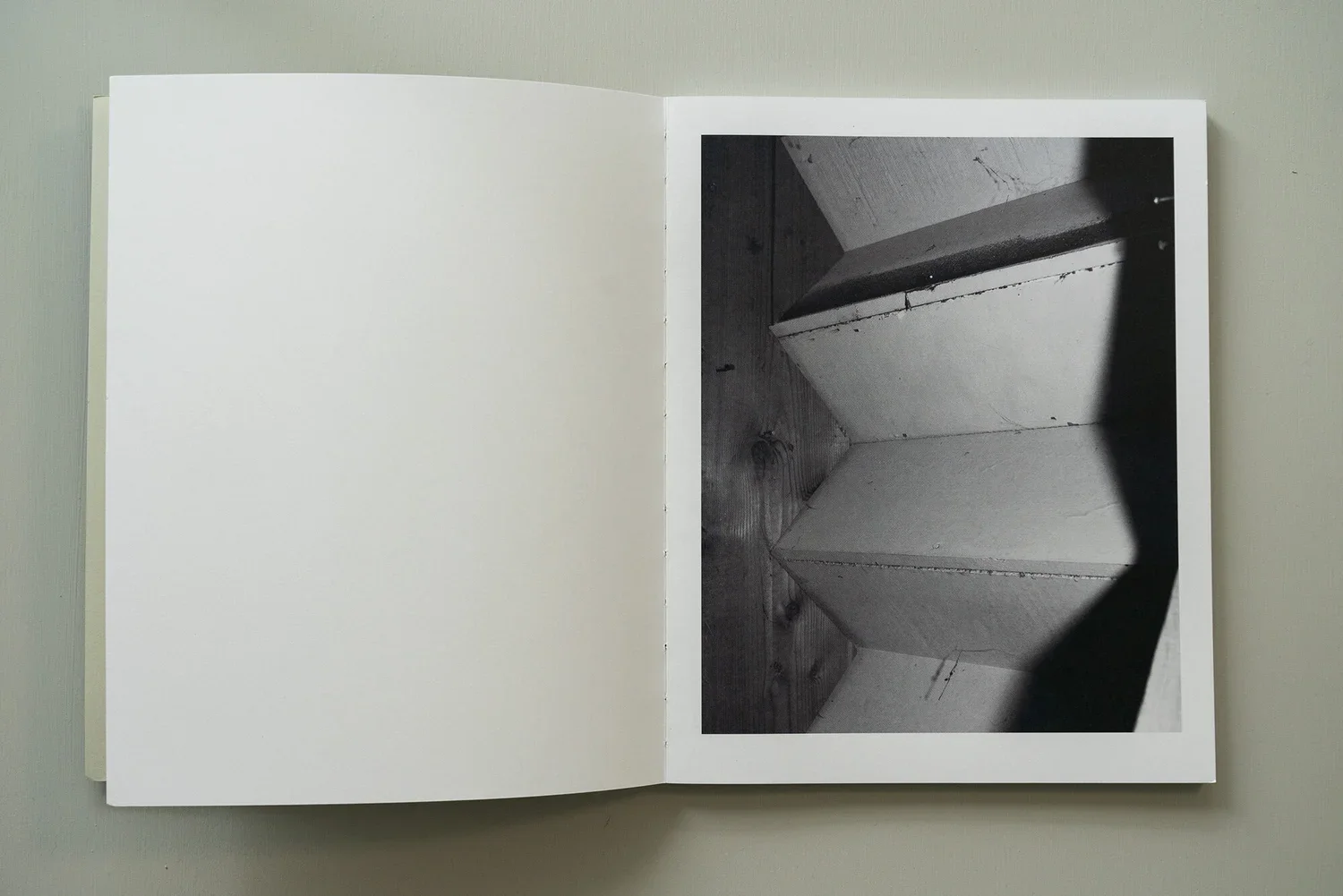

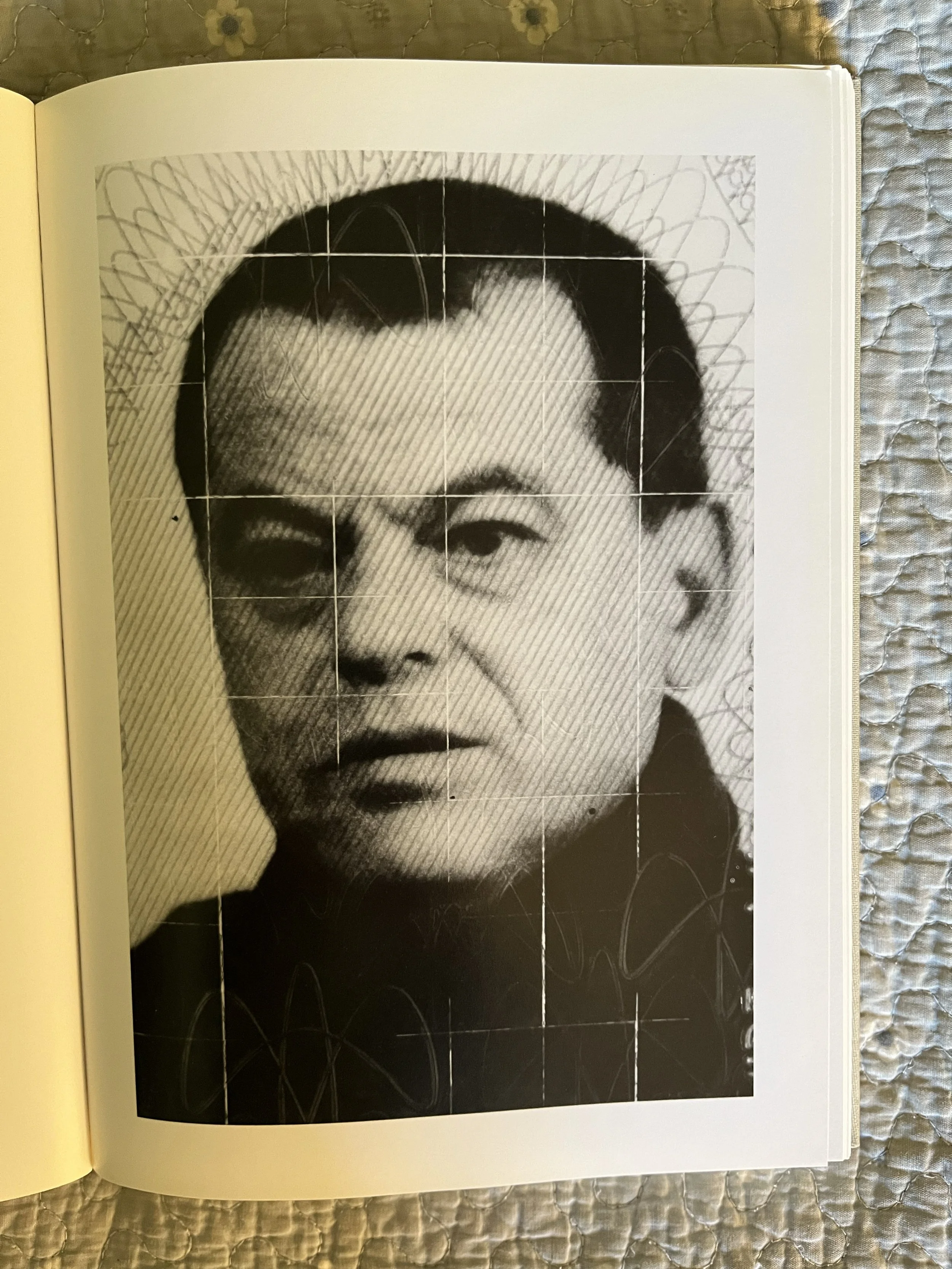

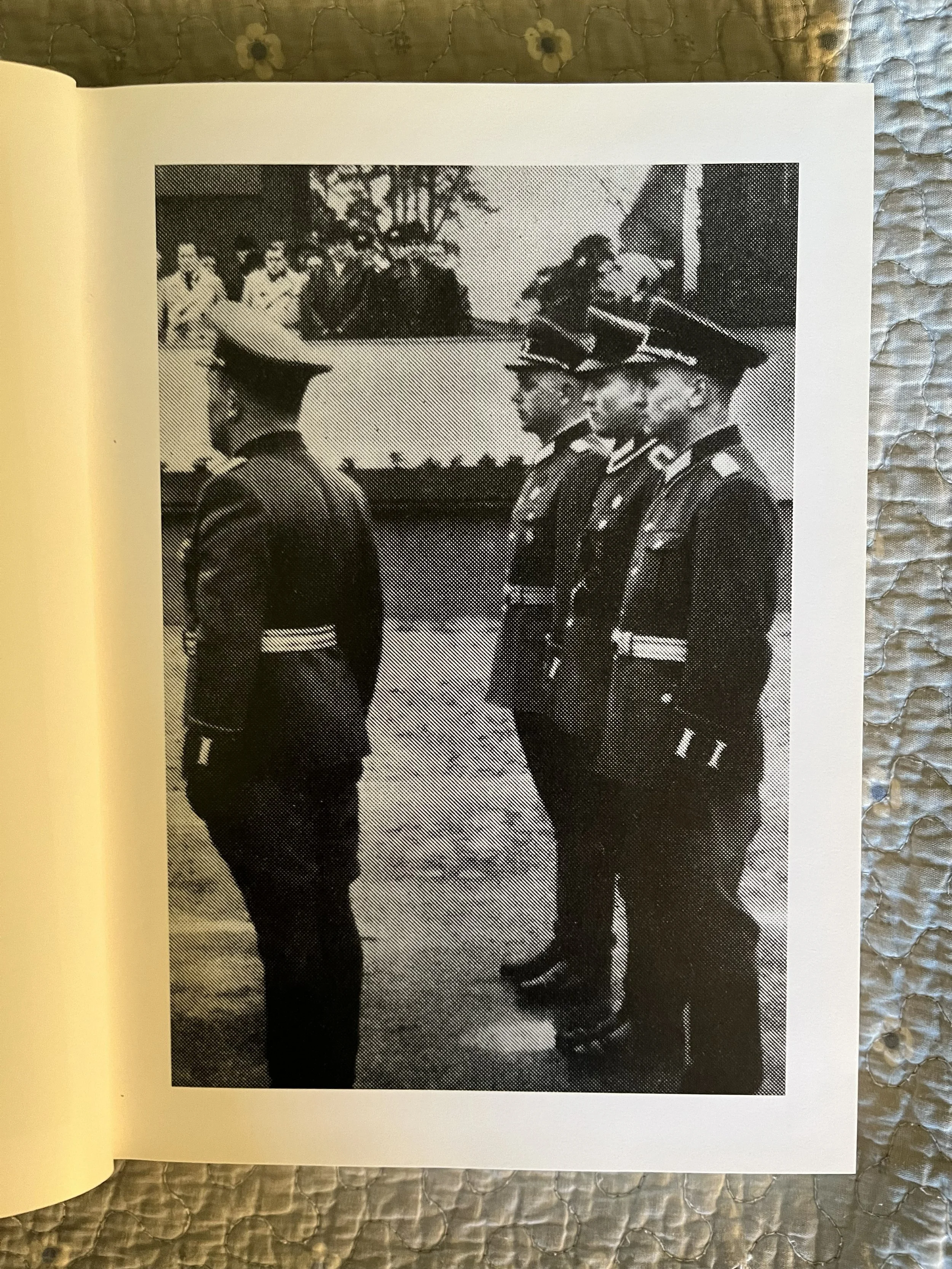

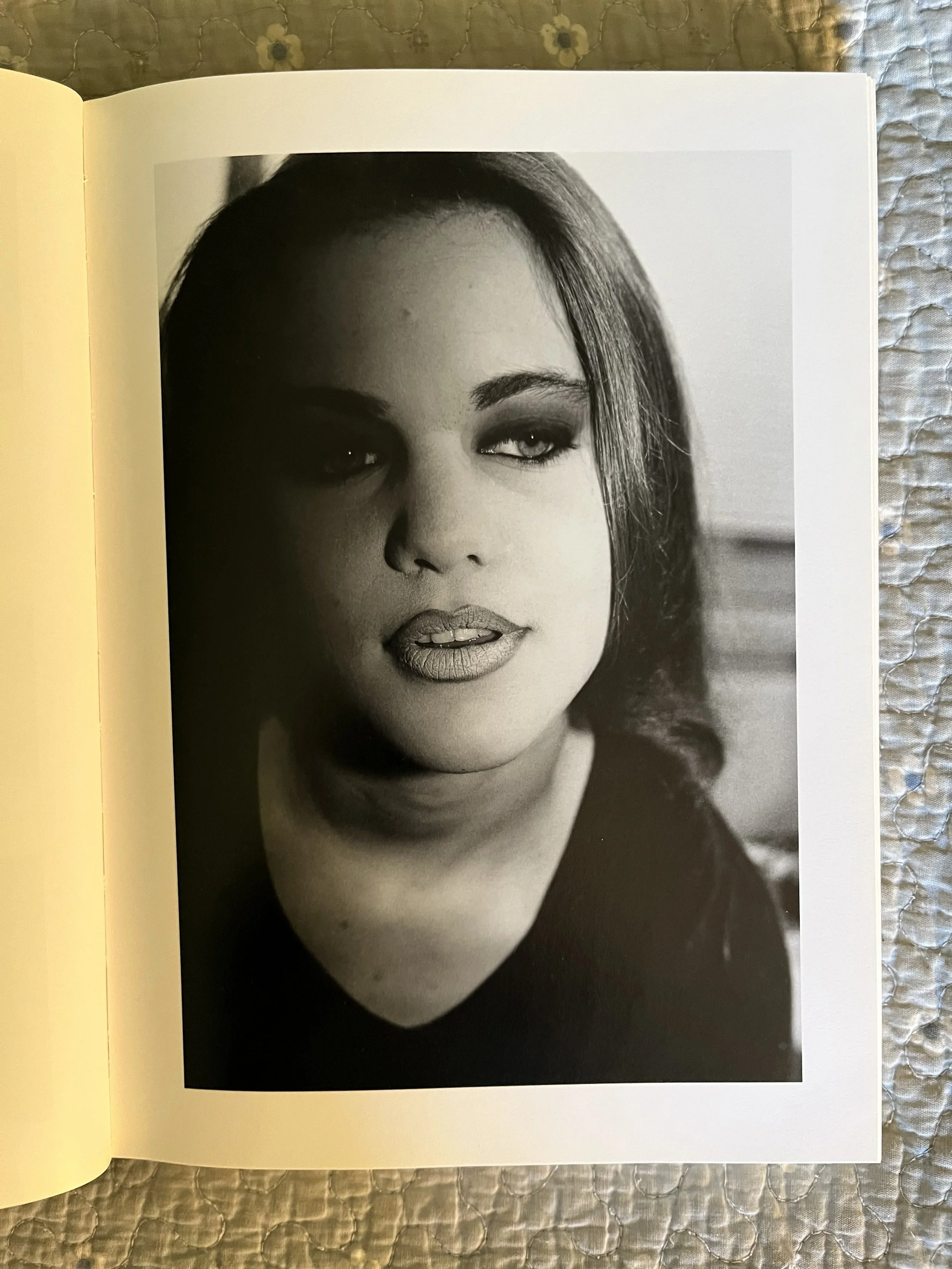

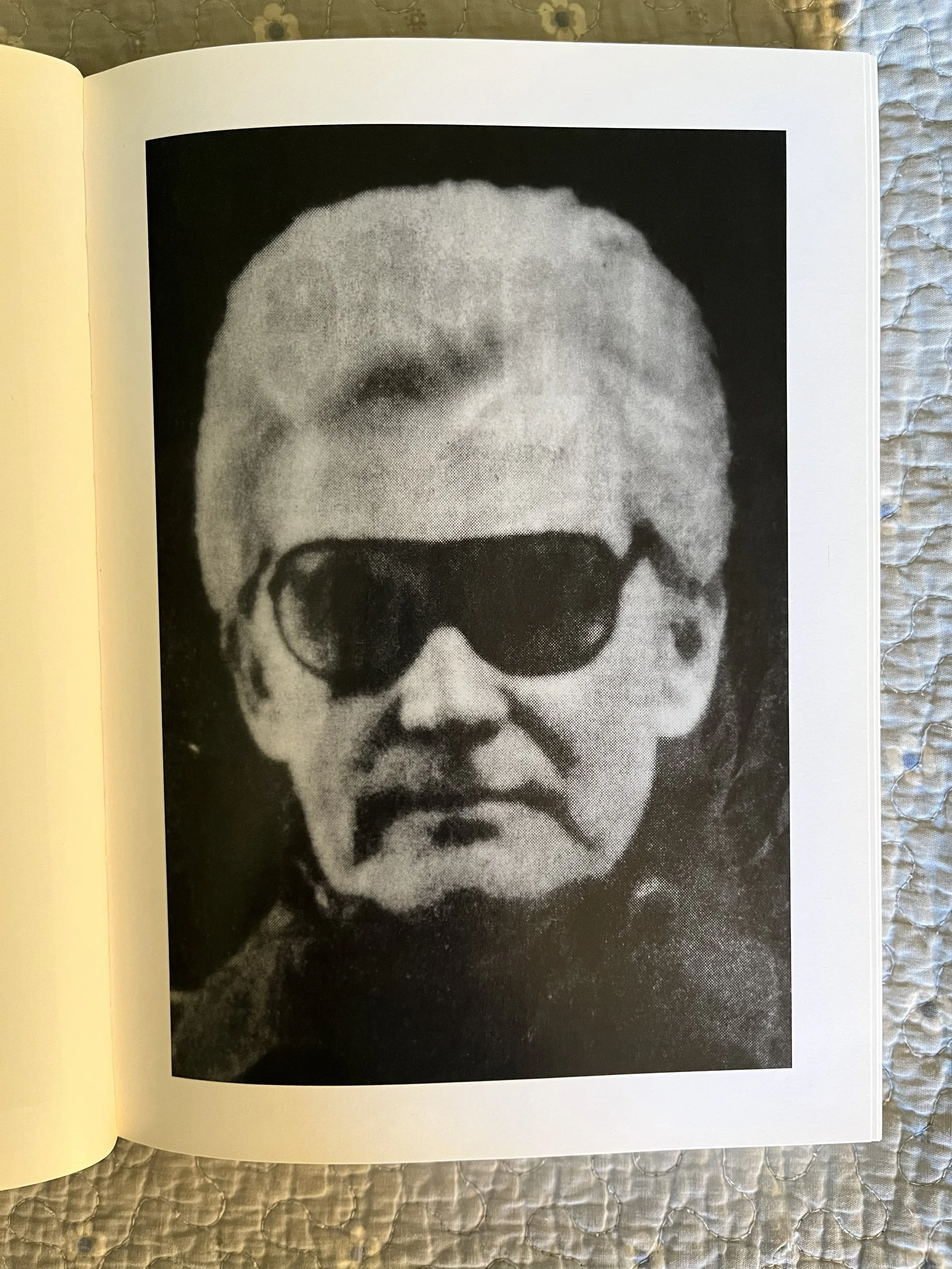

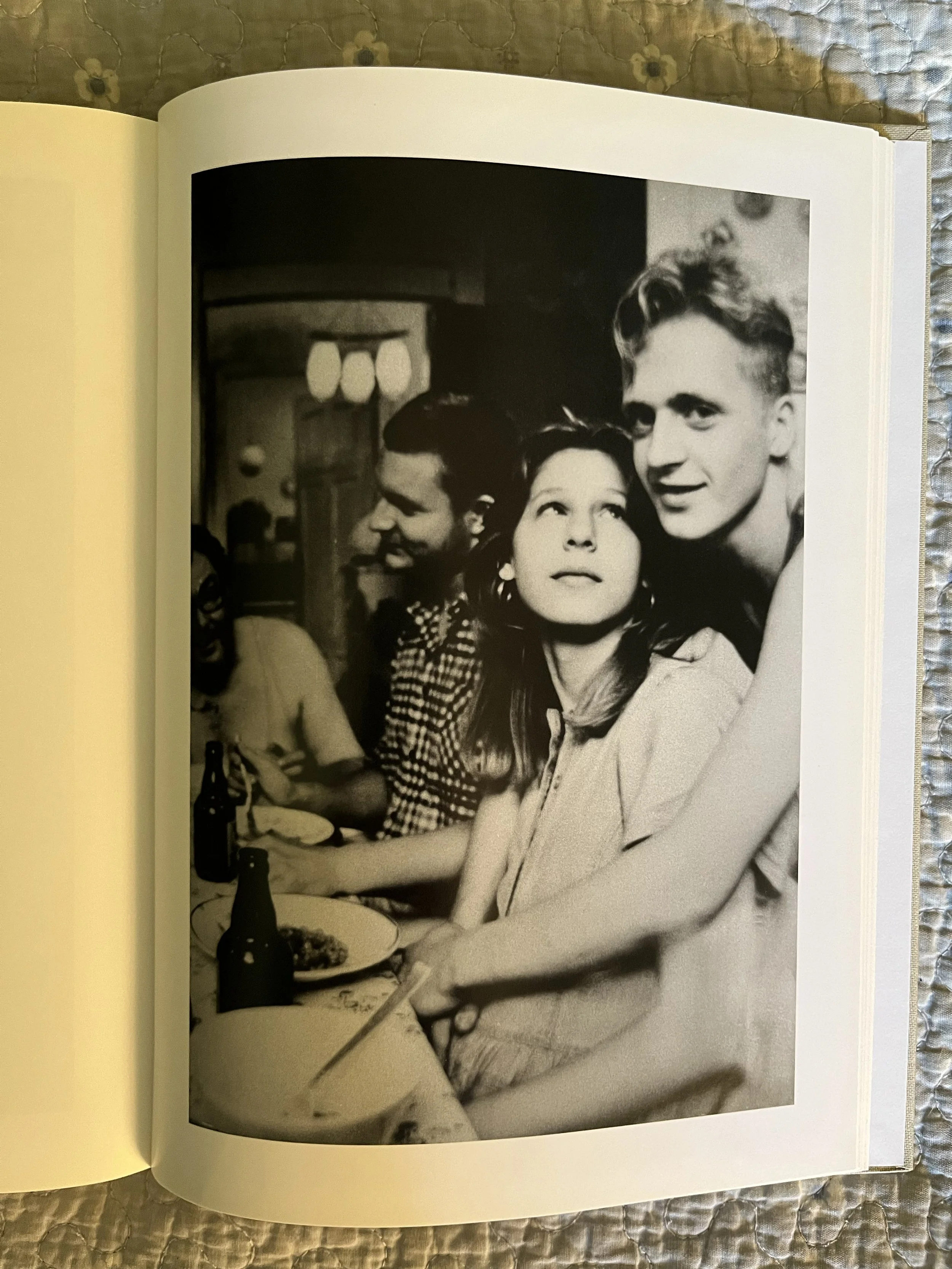

Blake Andrews. from asa nisi masa.

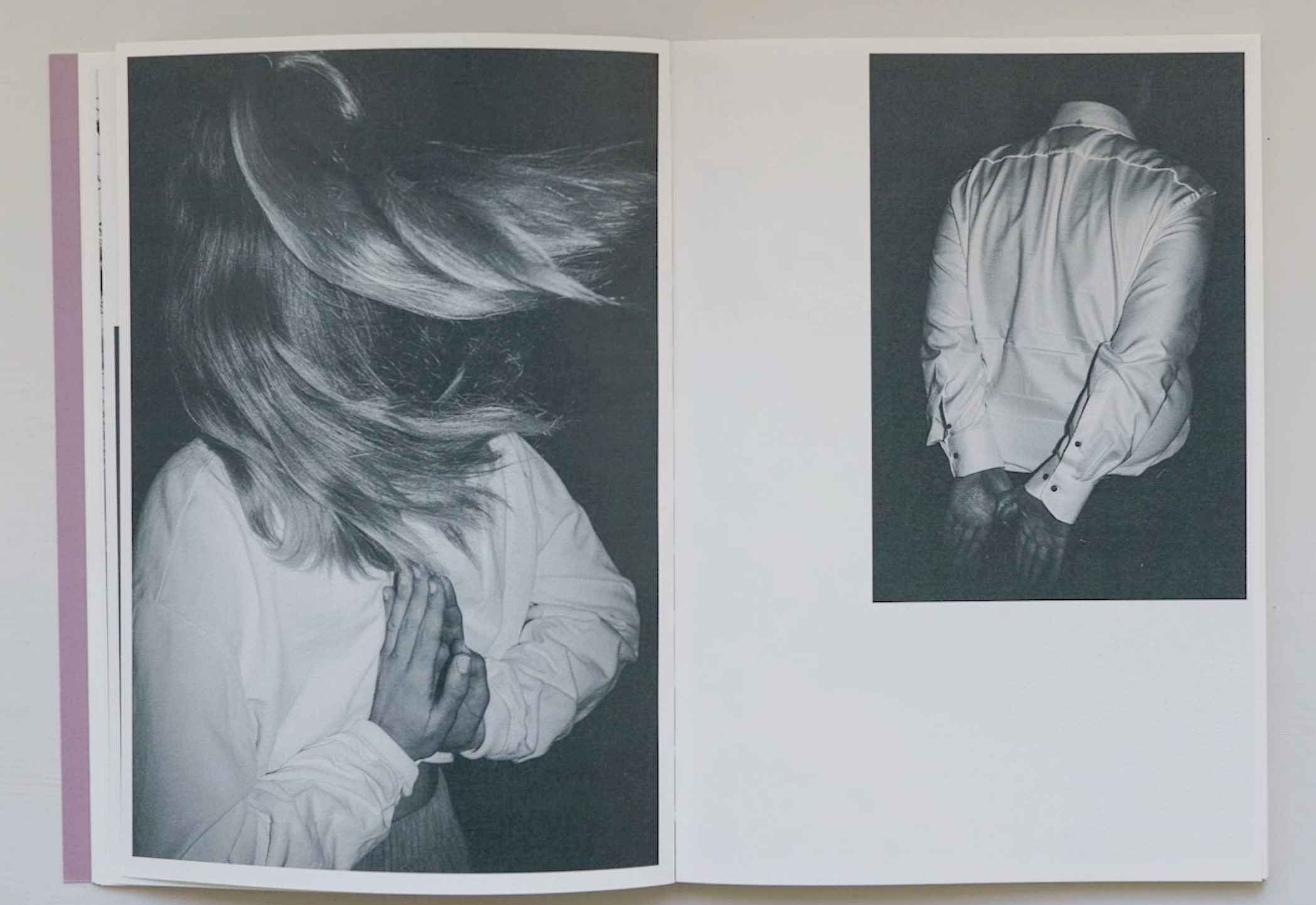

After looking carefully through his book, I cannot tell you how happy I am knowing that Blake is out there somewhere with his camera, perhaps right now. I could not conceive of the photos in asa nisa masa happening without shooting that many pictures. The book is a collection of some of the rarest coincidences, oddities, surreal moments, and curious visual rhymes I’ve seen. What came to mind when I lay down the book was the line by Jim Morrison: “This is the strangest life I’ve ever known.”

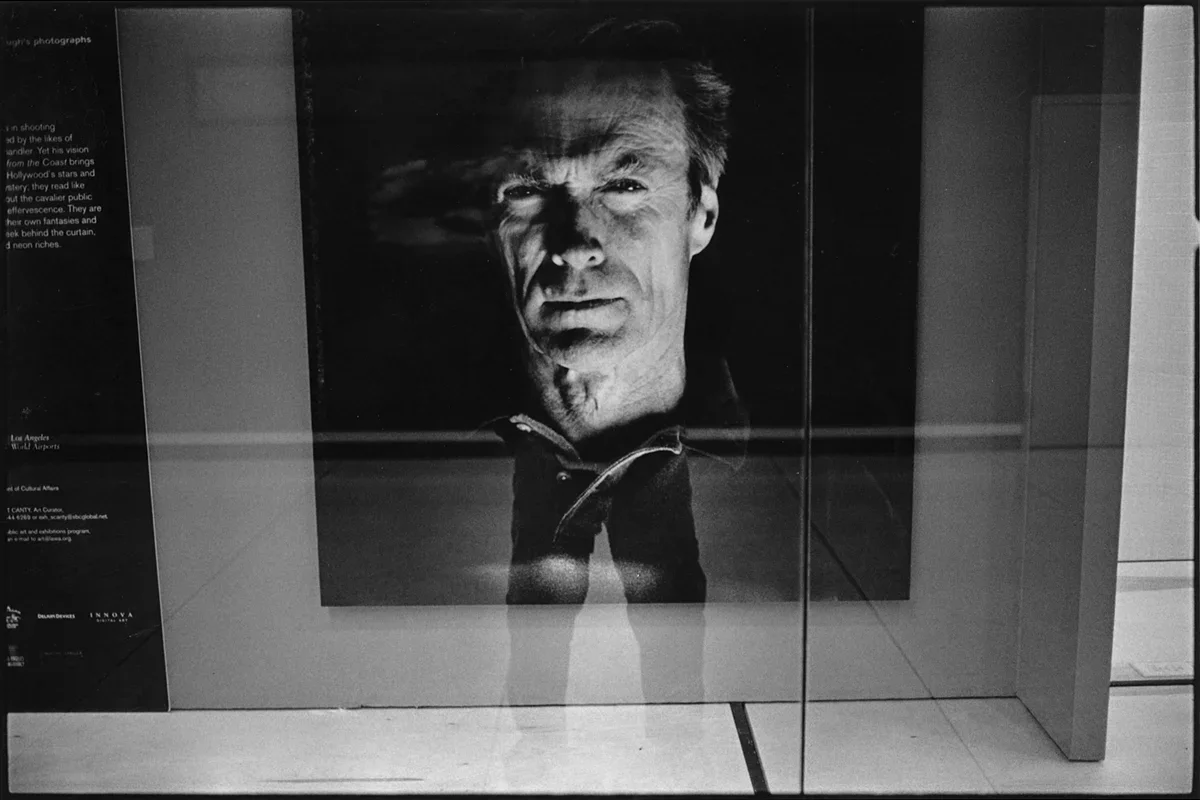

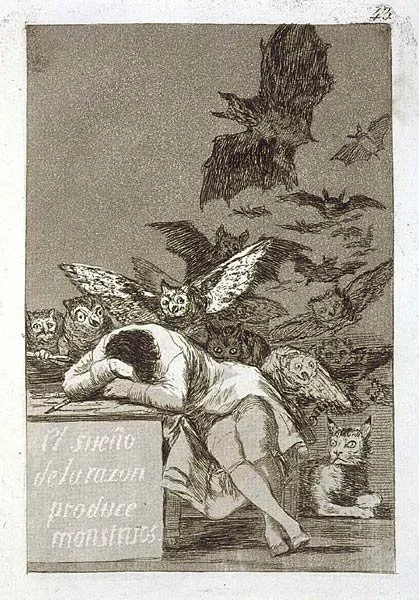

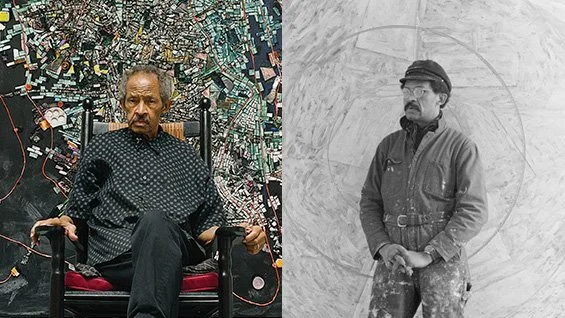

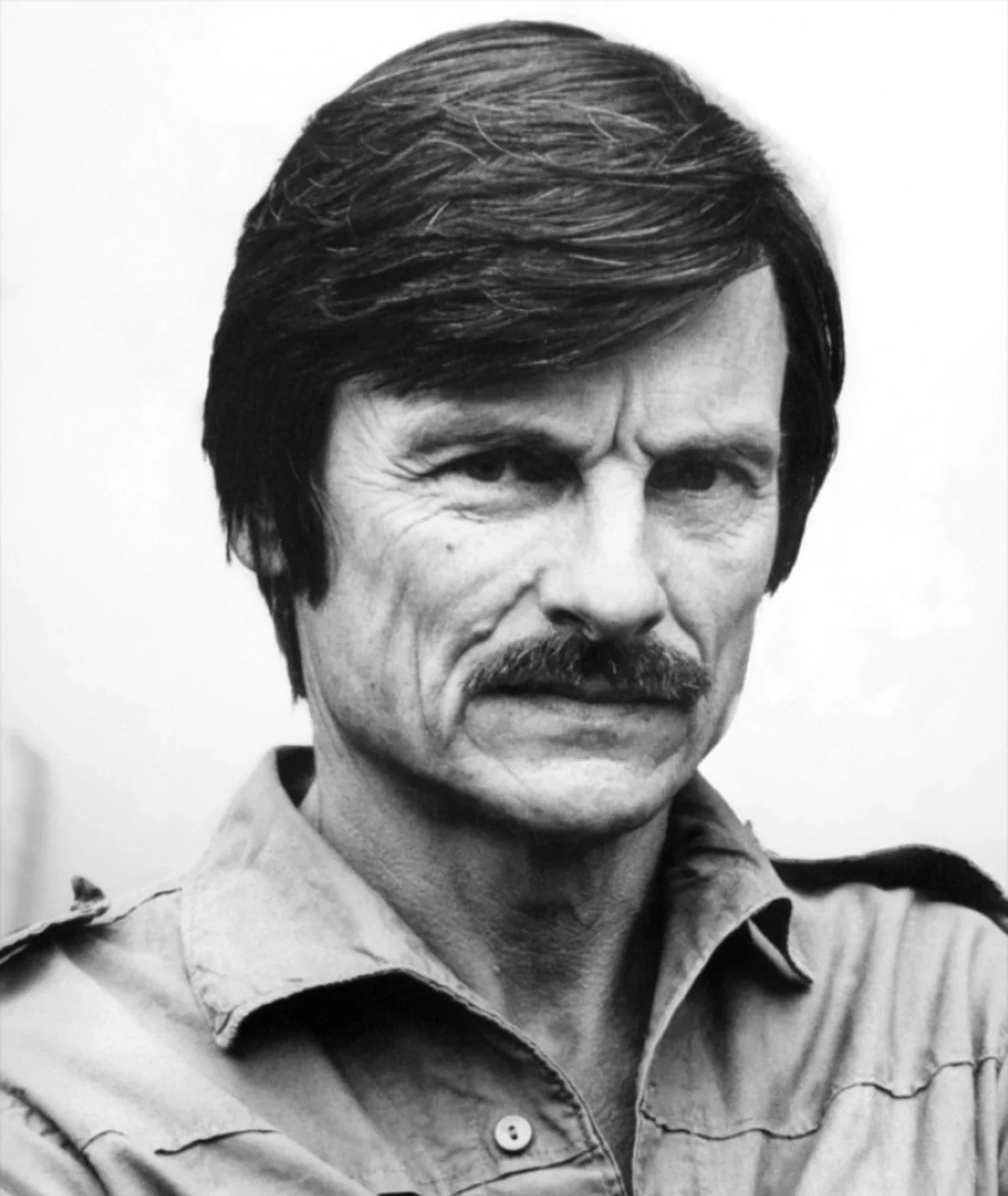

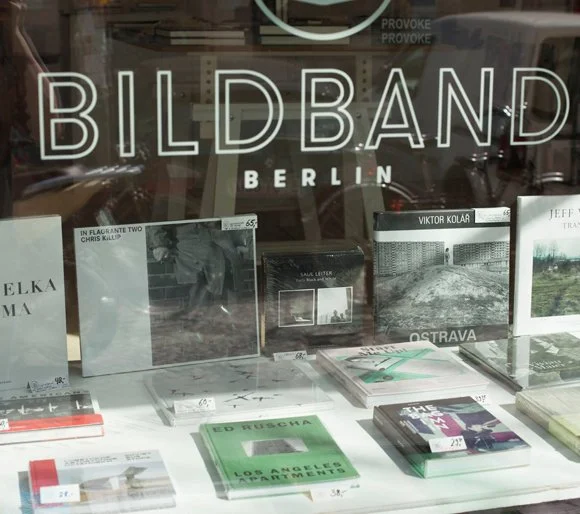

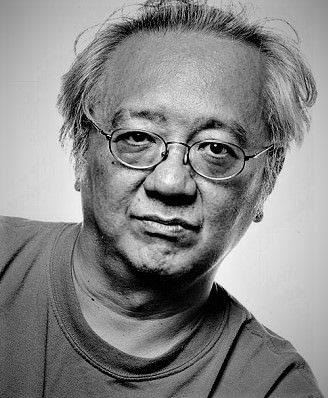

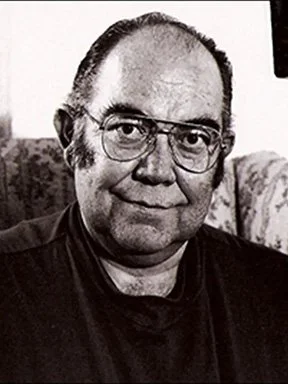

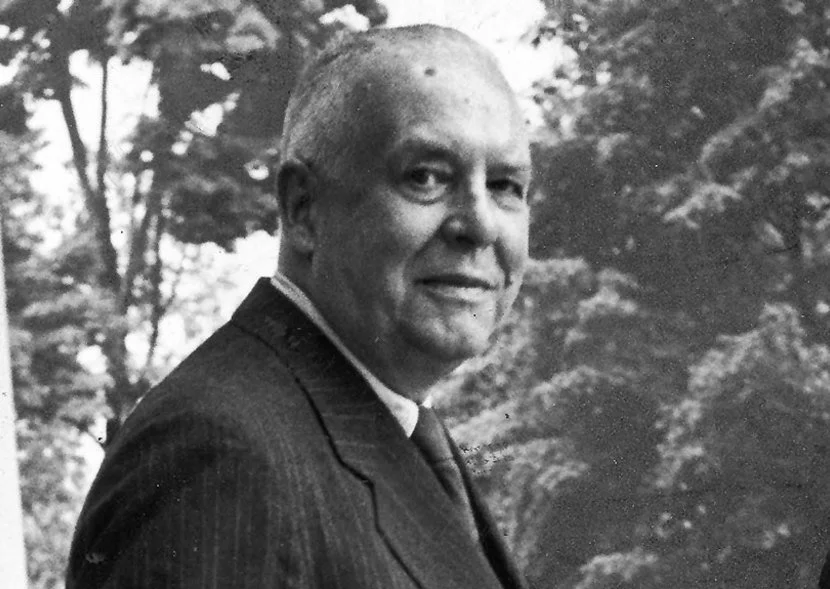

Lee Friedlander.

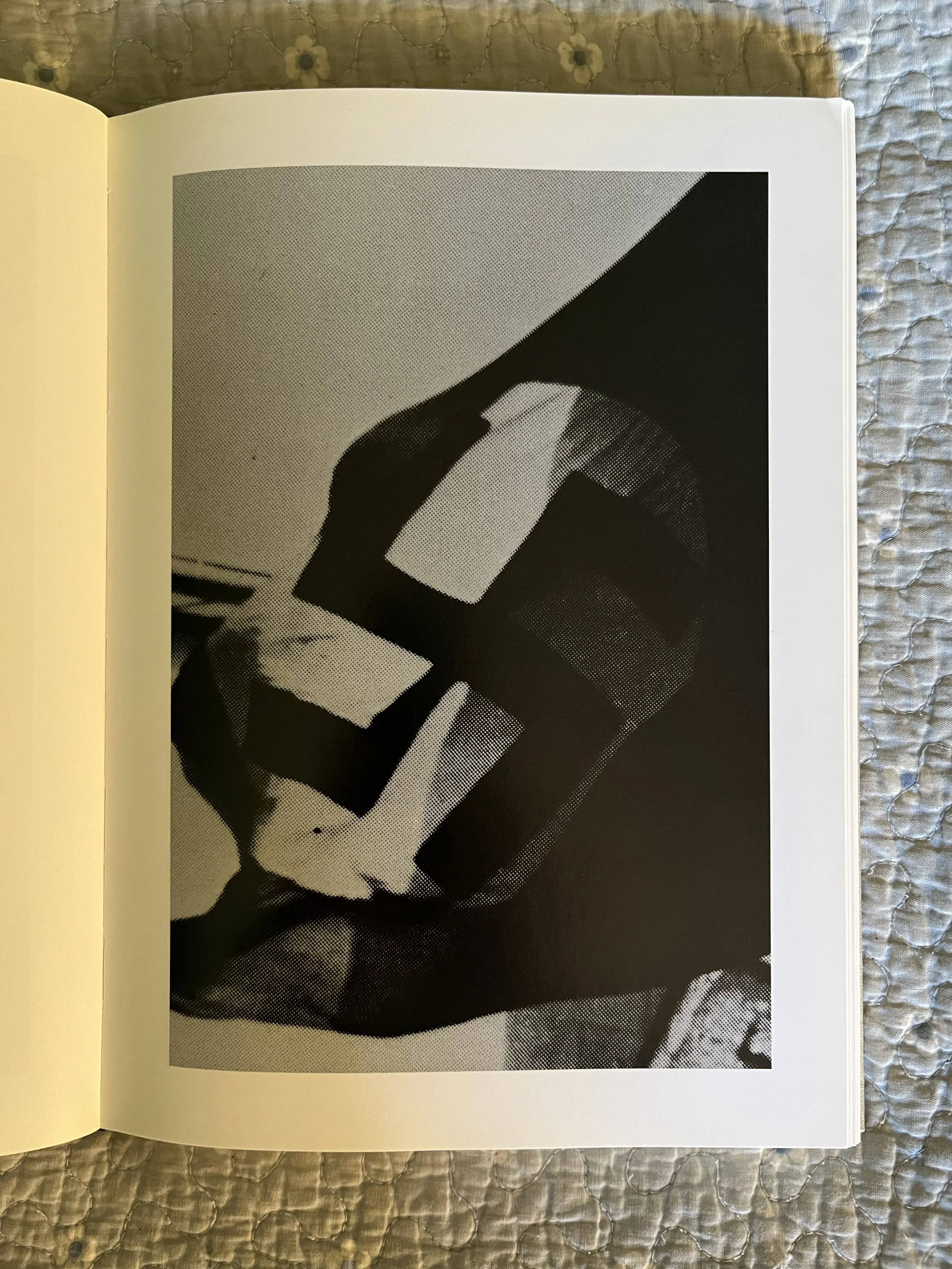

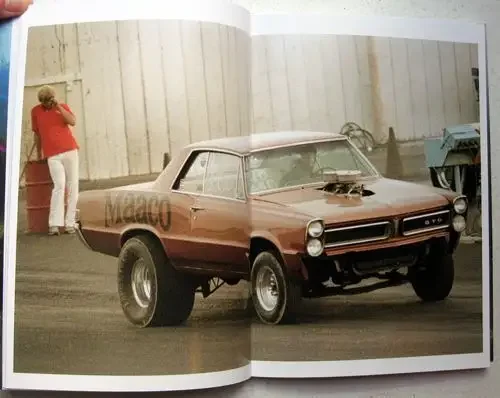

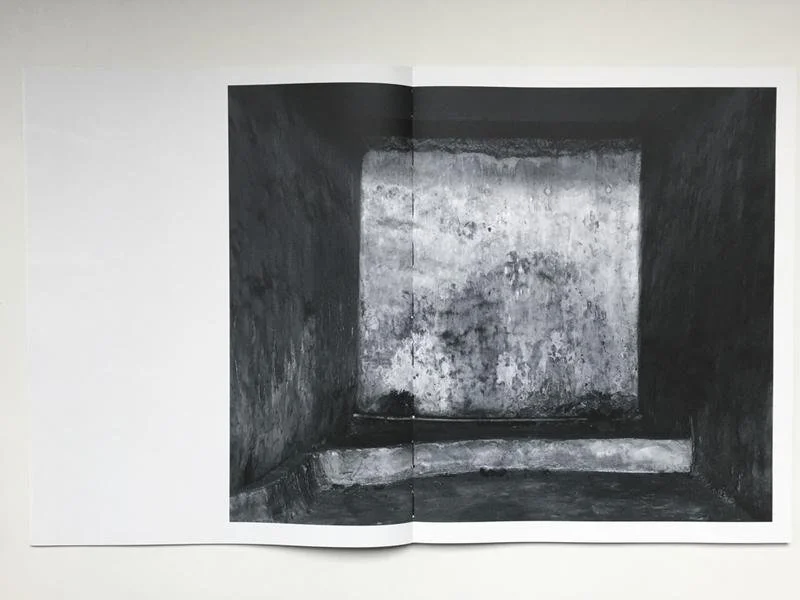

If there is an ancestor to this work—and all our work has ancestors, whether we’re aware of them or not—it would be a single photograph by Lee Friedlander of a cloud balanced on the edge of a triangular street sign. That playfulness is extended into an almost Shakespearean delight with visual rhyme that has a painted white line in the street continuing up into a white bag held by a woman in the crosswalk. Or the mimicry of a dark and light striped lego device in the hands of a child echoing the dark and light bands of wood venetian blinds behind him. Or a conduit pipe continuing as a flute in the hands of a busker. These optical coincidences, which are just one theme within the work, live only because Blake saw and photographed them.

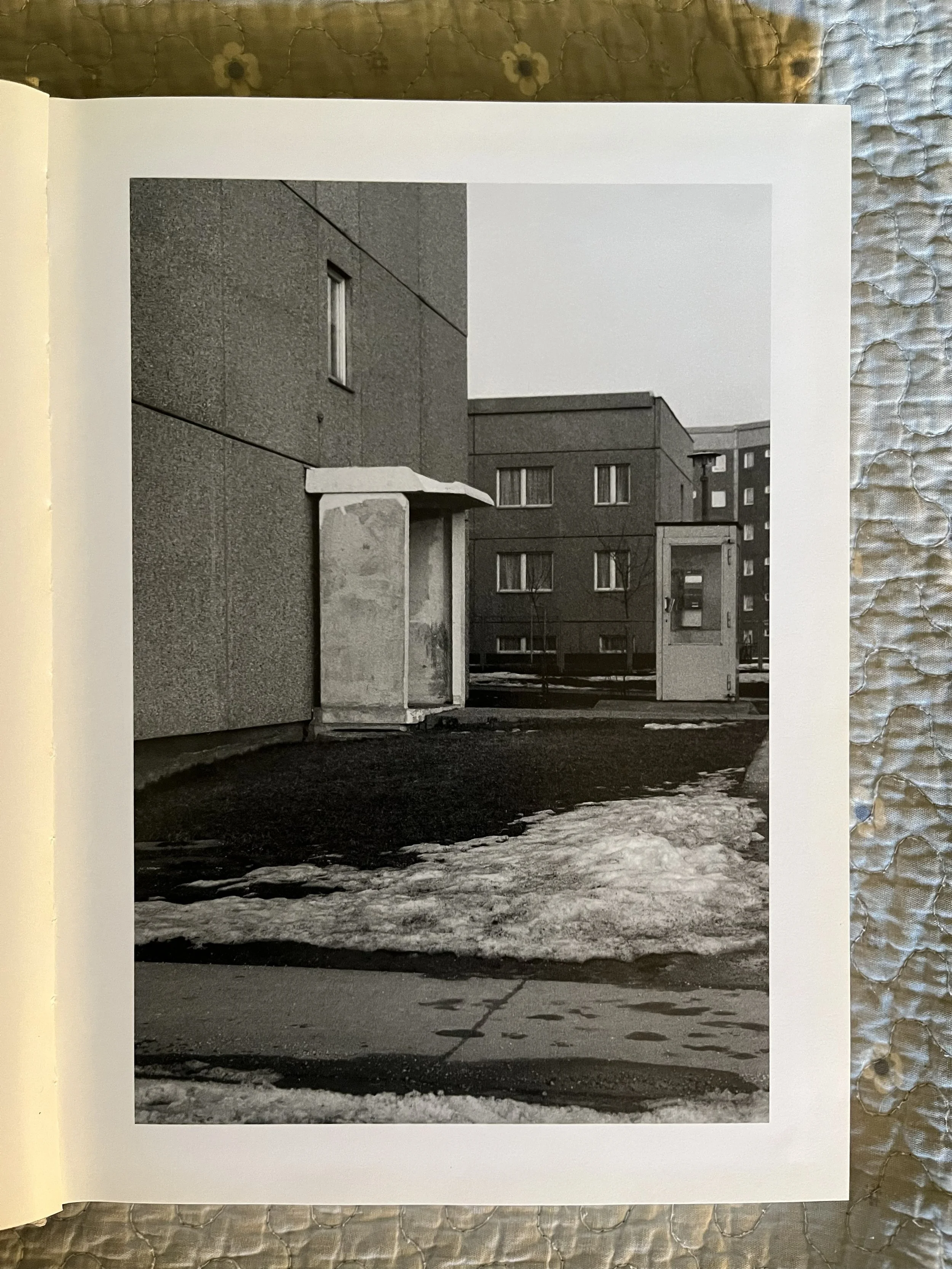

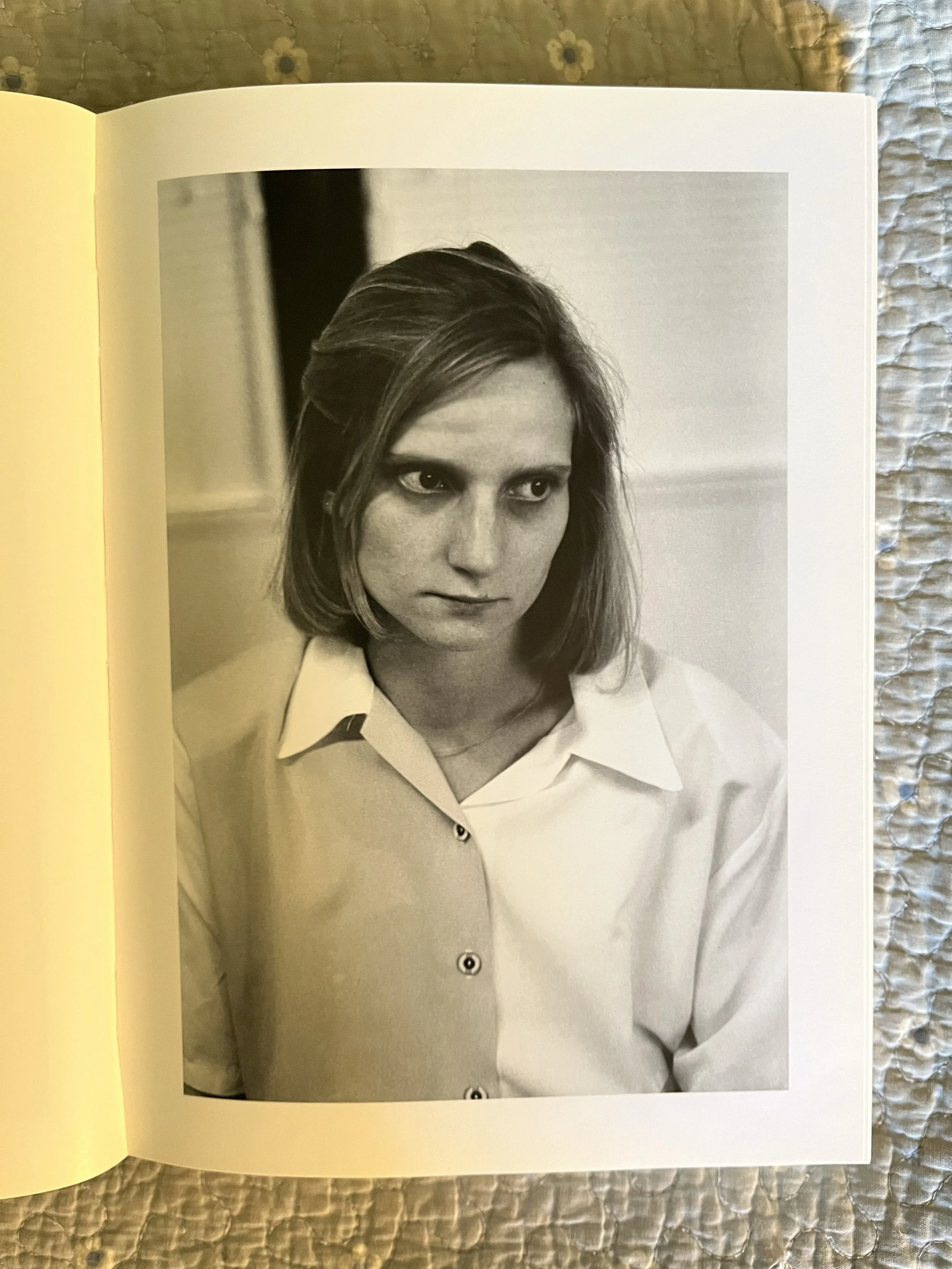

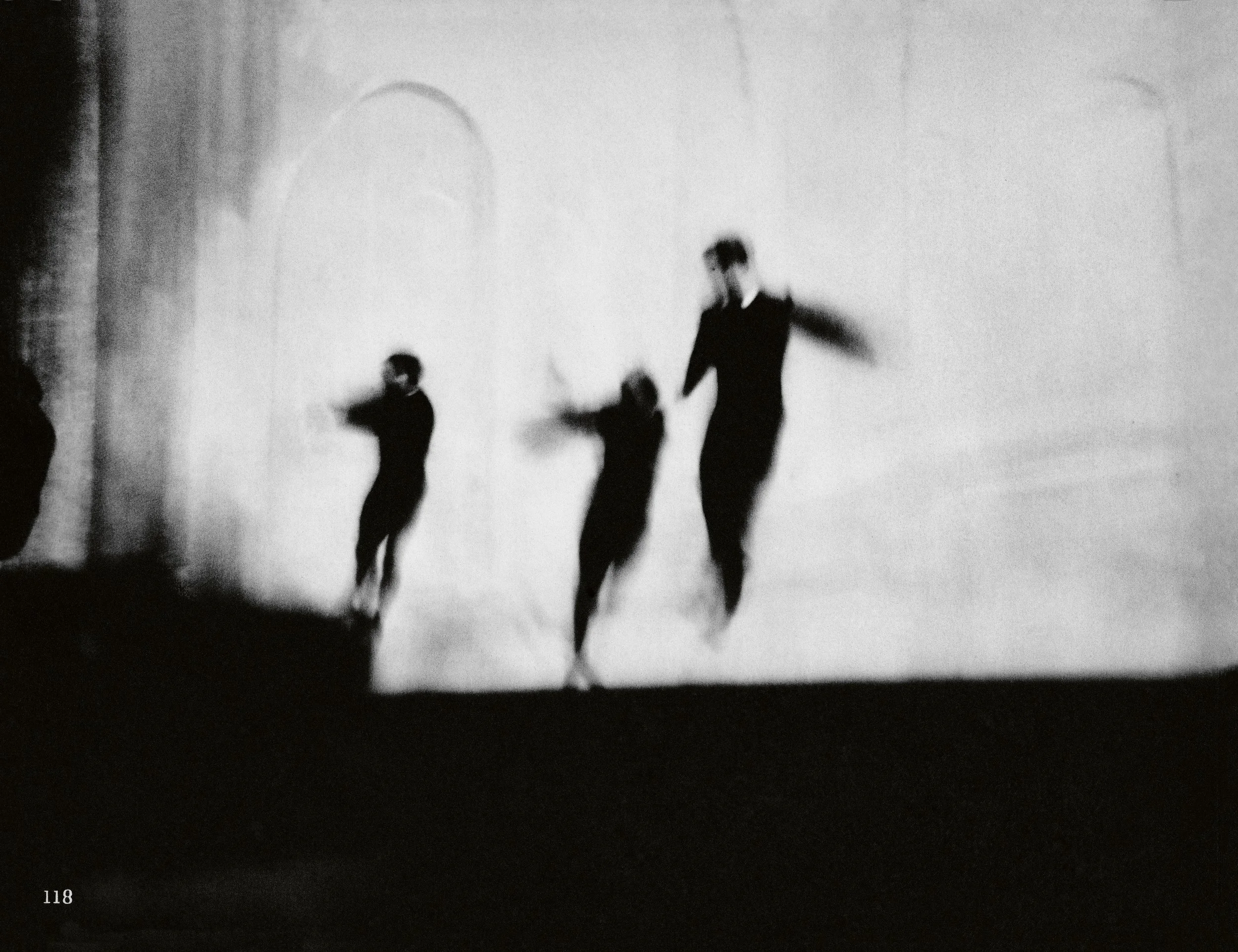

Blake Andrews. from asa nisi masa.

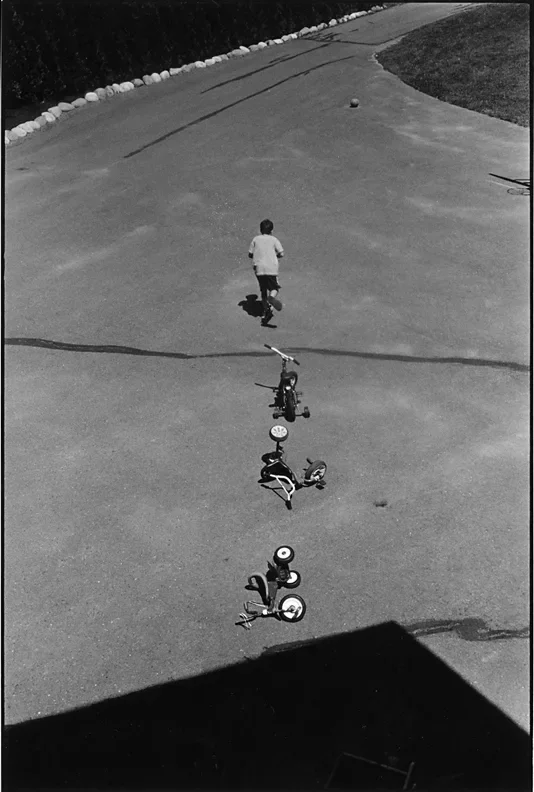

There are several other kinds of serendipitous visual events besides such rhymes, but I’m not sure I could categorize them. Some have one object lining up with another object, like an ad on a bus in the foreground lining up with the building behind it. Others include a child running who seems to be leaving a trail of crashed tricycles behind him. The book is a symphony of oddness. If you’re looking for a clue, the title is a magical chant with no actual meaning from the childhood scenes in Fellini’s 8 1/2. How great is that?

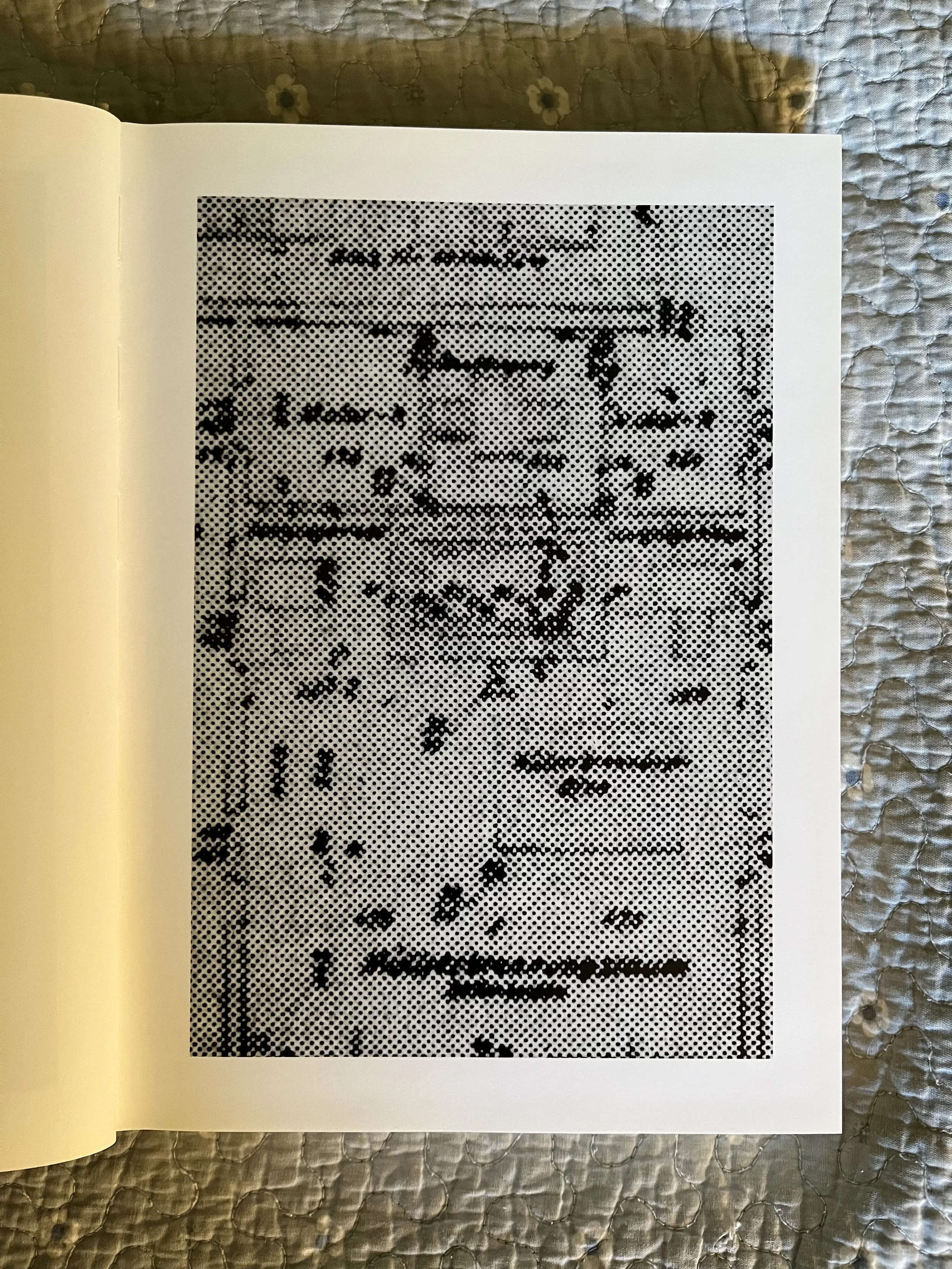

Blake Andrews. from asa nisi masa.

A myriad street photographers are out there trying to capture the decisive moment. Blake Andrews is out there weirding things up and sticking a pin into the balloon of a contemporary photography that has inflated itself with ultra-serious statements about politics and identity and social issues which photography (or art in general) never has been able to solve. That’s not to say there aren’t a few poignant moments in asa nisi masa or that it’s not serious photography. But serious can also be joyful, perplexing, mind-bending, and even give us a laugh now and then, as well as make us shake our head at just how many incomprehensible moments occur in this life.

Blake Andrews. from asa nisi masa.

The book is sold out on the Eyeshot website. I’m not sure if copies of the book are otherwise available, but you might reach out to Blake via @swerdnaekalb on Instagram to find out. This is a great edit, beautifully printed in Italy, and it made me happy. Also, do not fail to follow Blake’s reviews of photobooks on the Collector Daily web site, which hosts some of the best writing on photography today.