“Unity, justice, and freedom for the German fatherland. Let us all strive for this, brotherly, with heart and soul. Unity, justice, and freedom are the pillars of this bliss. Flourish in the splendor of this bliss, flourish, German fatherland.”

-Google translation of a plaque depticted in the book Ein-Heit

Please excuse the weird moire pattern in this photo. Pretty, but not real.

I feel compelled to talk about reading the photobook Ein-Heit (Scalo, 1996) in this blog post. I will surely fail. Except I won’t. Because despite the fact that I don’t recognize many people and things in this book, despite the fact that I’m not German, or perhaps even more importantly not a Berliner, and I don’t know the references, and I don’t know the language, I still don’t believe Mr. Schmidt created this book with the idea that any serious attempt at reading it would lead to failure, whatever the outcome.

And yet, Ein-Heit is so weighty in subject matter, so large, so obviously complex, and so laden with meanings that failure always feels like a distinct possibility when I pick up this book. However, my experience with it has always been exceedingly gratifying, no matter how impenetrable the mystery of it sometimes feels.

But it’s not impenetrable. All you have to do is turn the pages.

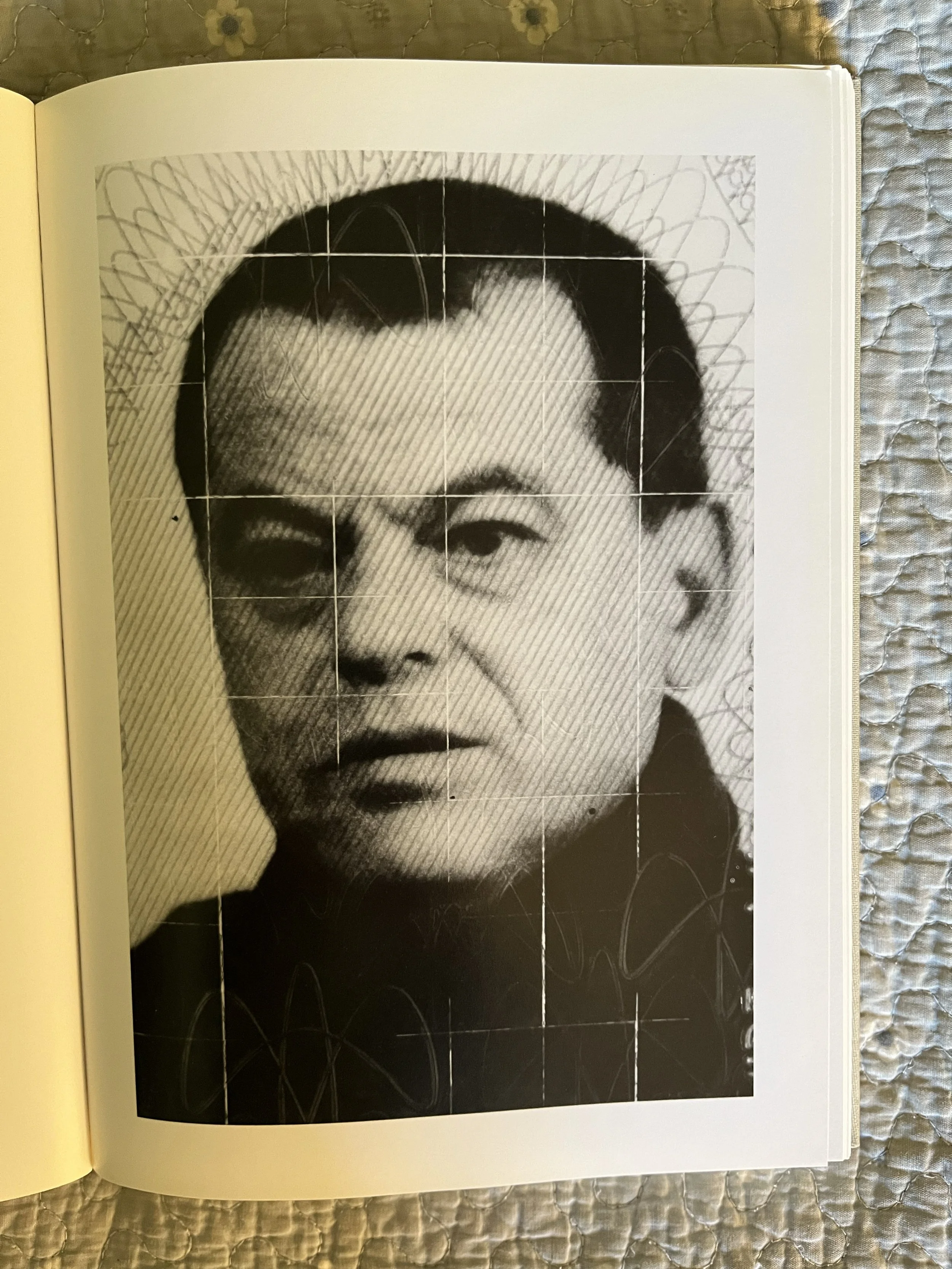

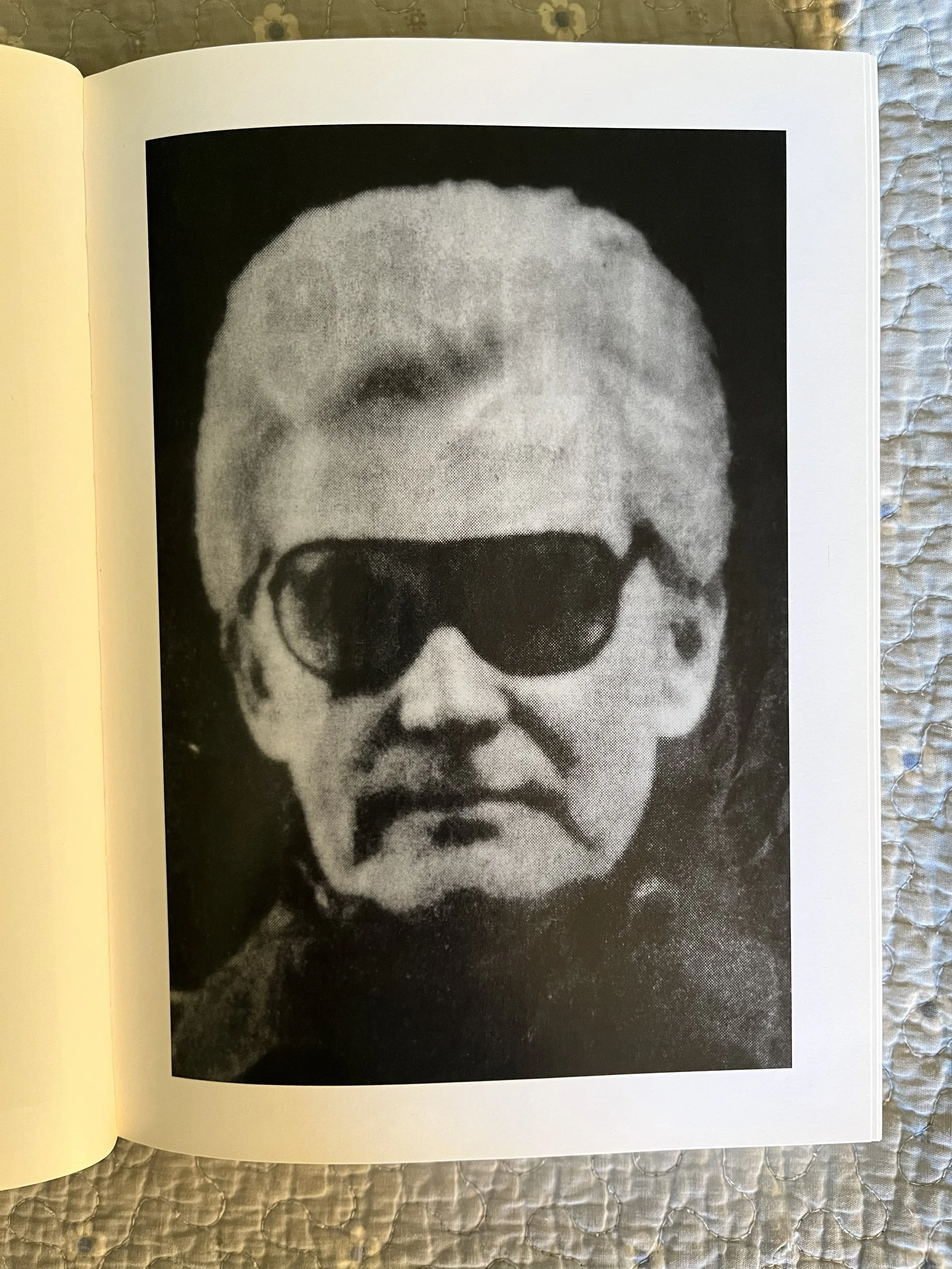

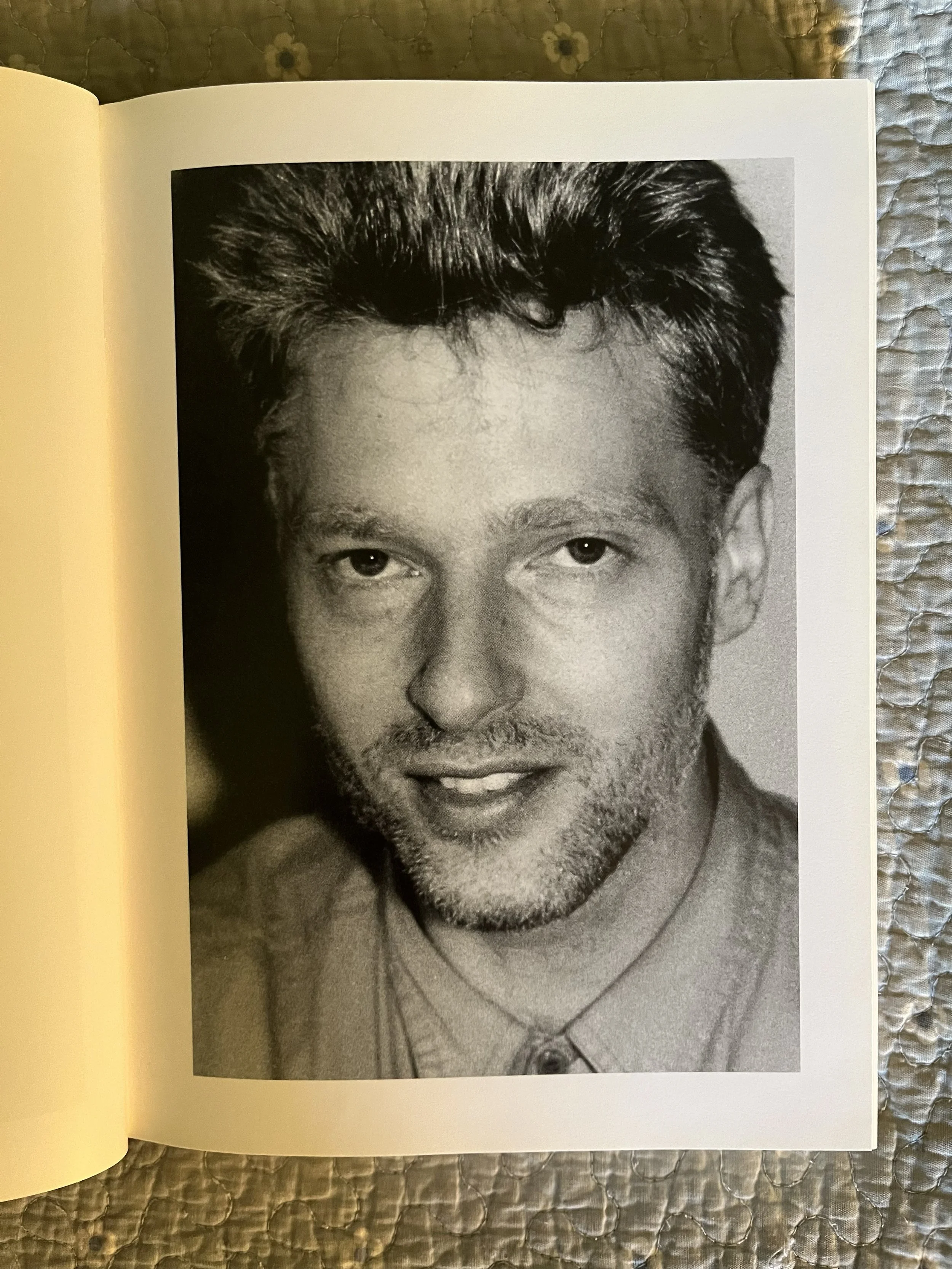

A photo of Michael Schmidt included in Ein-Heit.

The German word einheit means unity. But with the added hyphen, it reads to me more like one-ness. This is one of the richest book titles I know of, which is why I can’t abide the English version of the book, which has been retitled Un-i-ty. The whole point of the title in German is the subject matter of the book, which is the reunification of the two Germanys in 1990: the DDR (or East Germany, as we used to say), and the BDG (or West Germany). There were two Germanys—hence the two word parts joined by a hyphen—not three, as implied by Un-i-ty. (I hope Herr Schmidt didn’t pick the English title.)

Ein-Heit the book feels epic. Not in the literal sense of the traditional epic form of poetry, which is a long narrative. There is no narrative here (thank God). But the book feels epic in scope, and in length, and in importance.

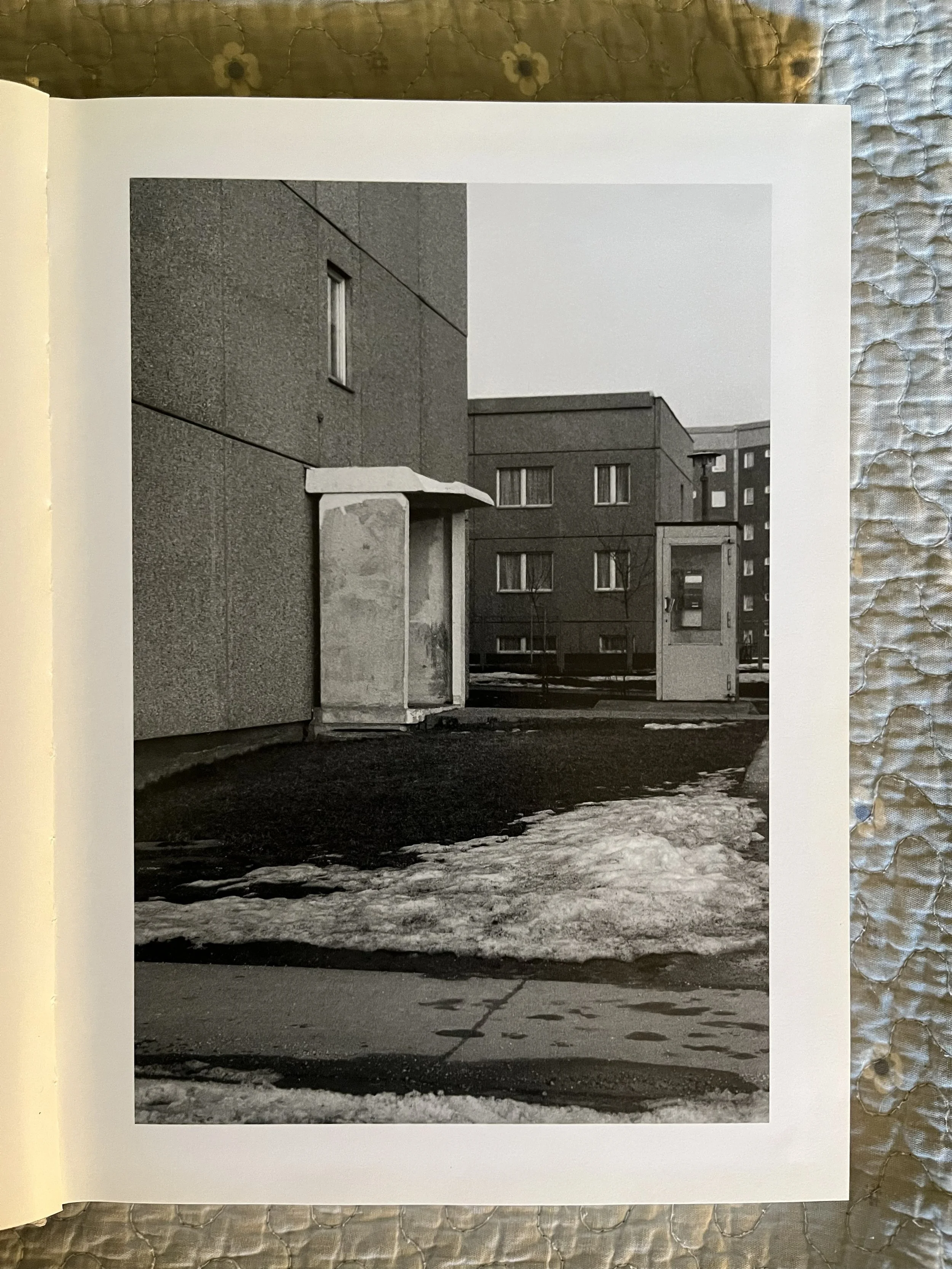

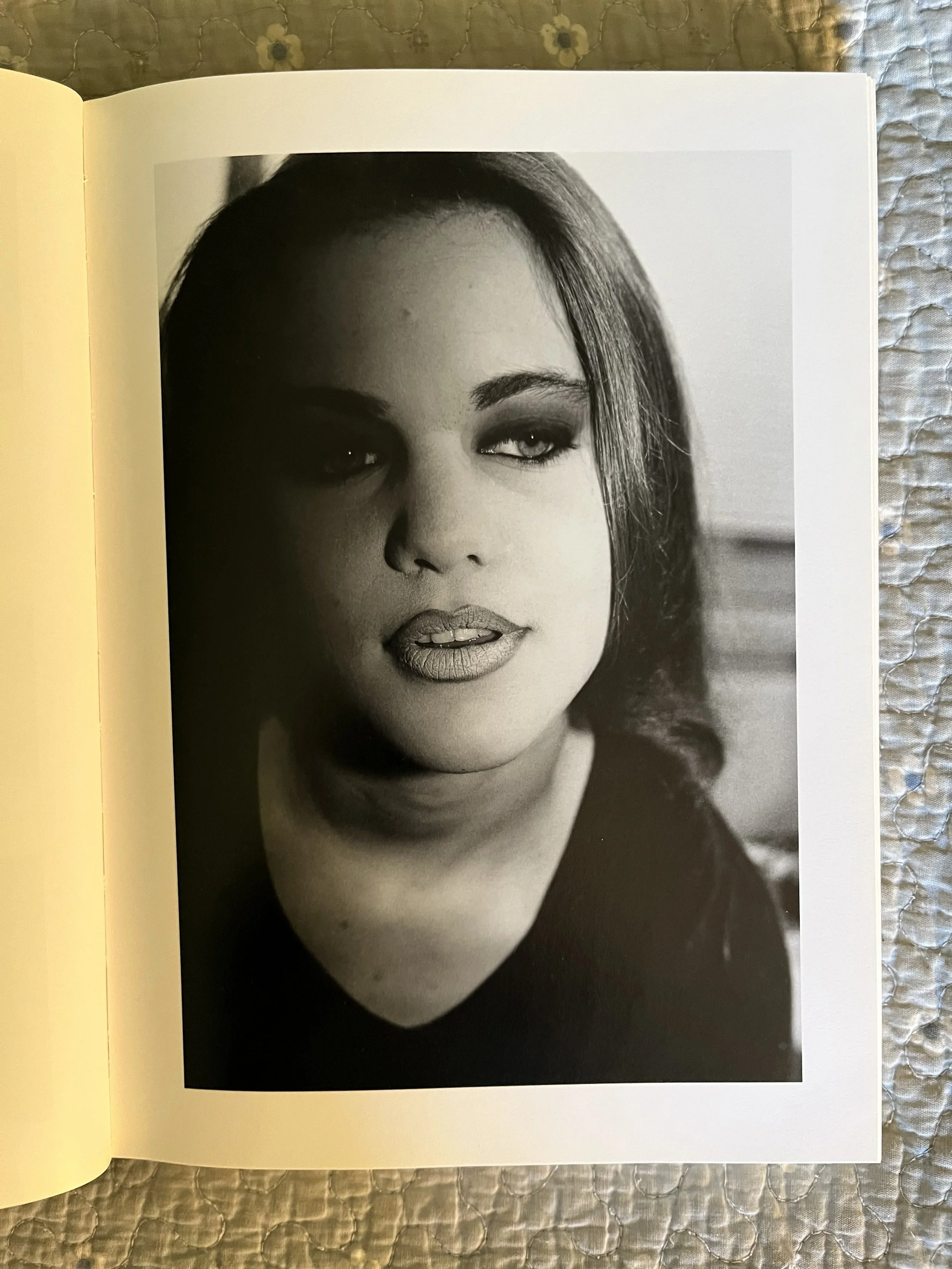

First photograph in Ein-Heit.

It starts off with three photos pretty clearly taken by Mr. Schmidt—many of the subsequent photos were not originally taken by him, but were photographs he photographed from what appears to be newspapers, magazines, and books, as indicated by the Ben Day dots. The first is a winter scene outside what appears to be an apartment complex. The second photo is of patterned window curtains. The third features patterned wallpaper and part of a table. So far, we’re not being “told” what we’ll find in the rest of the book.

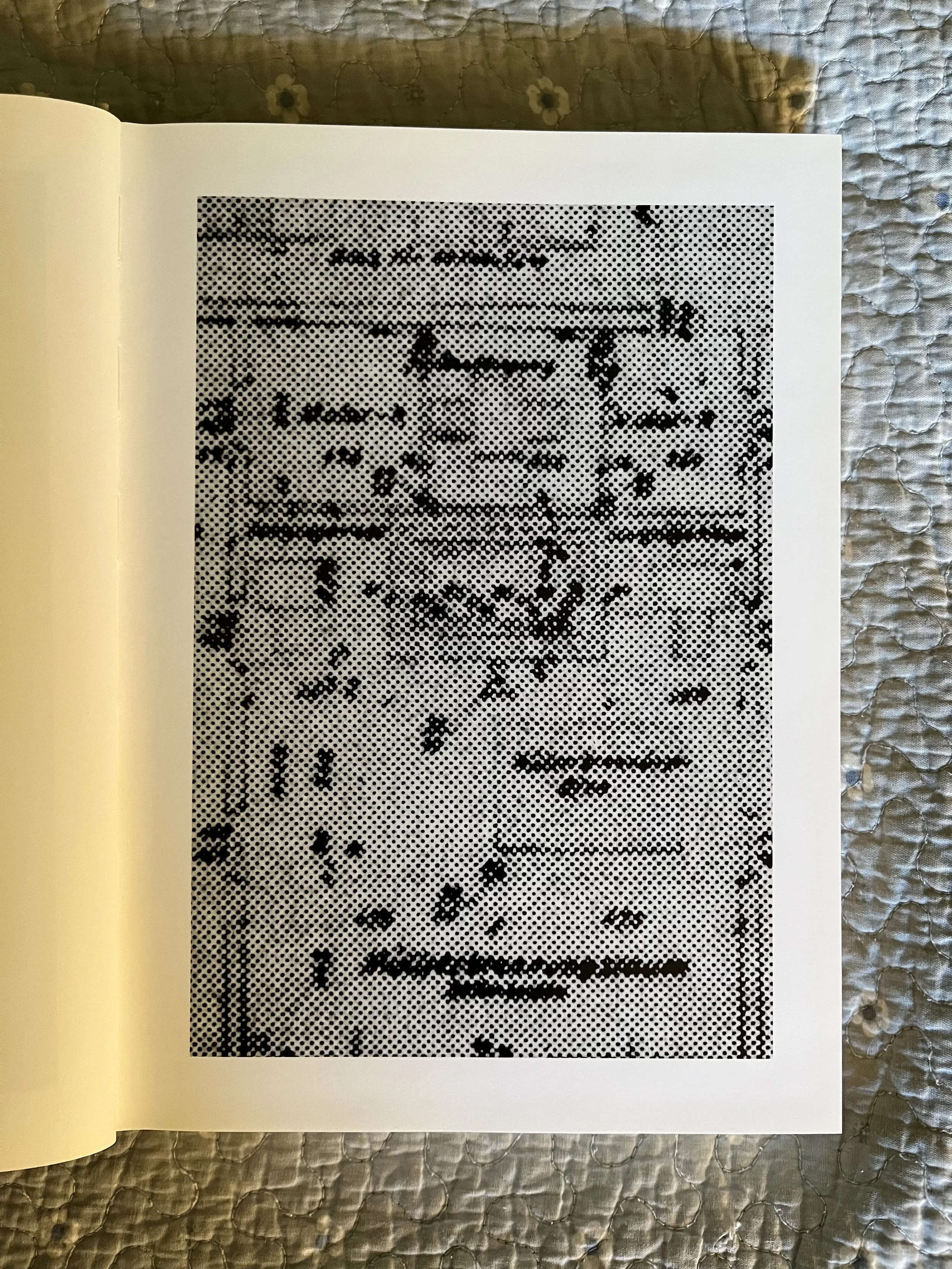

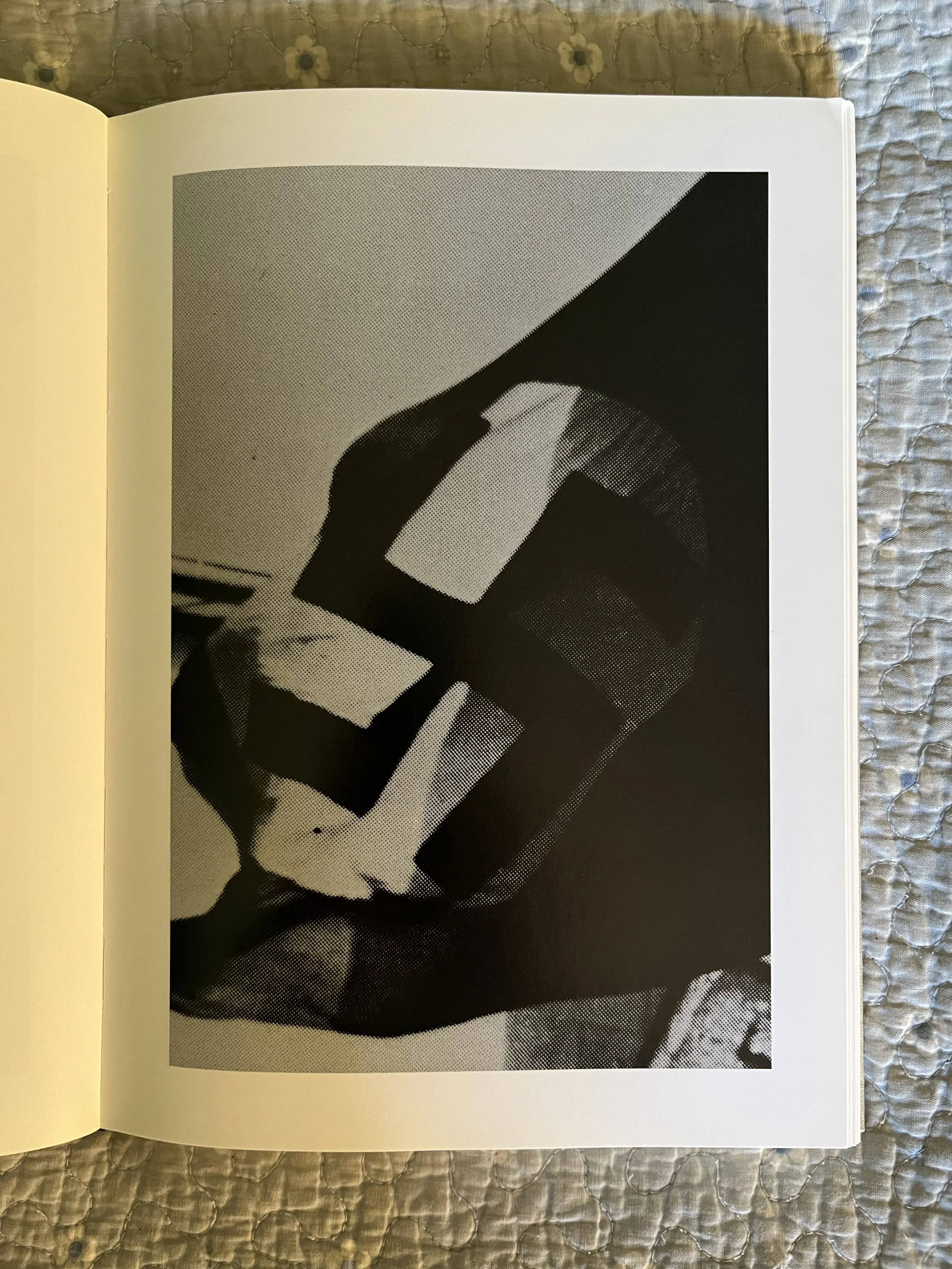

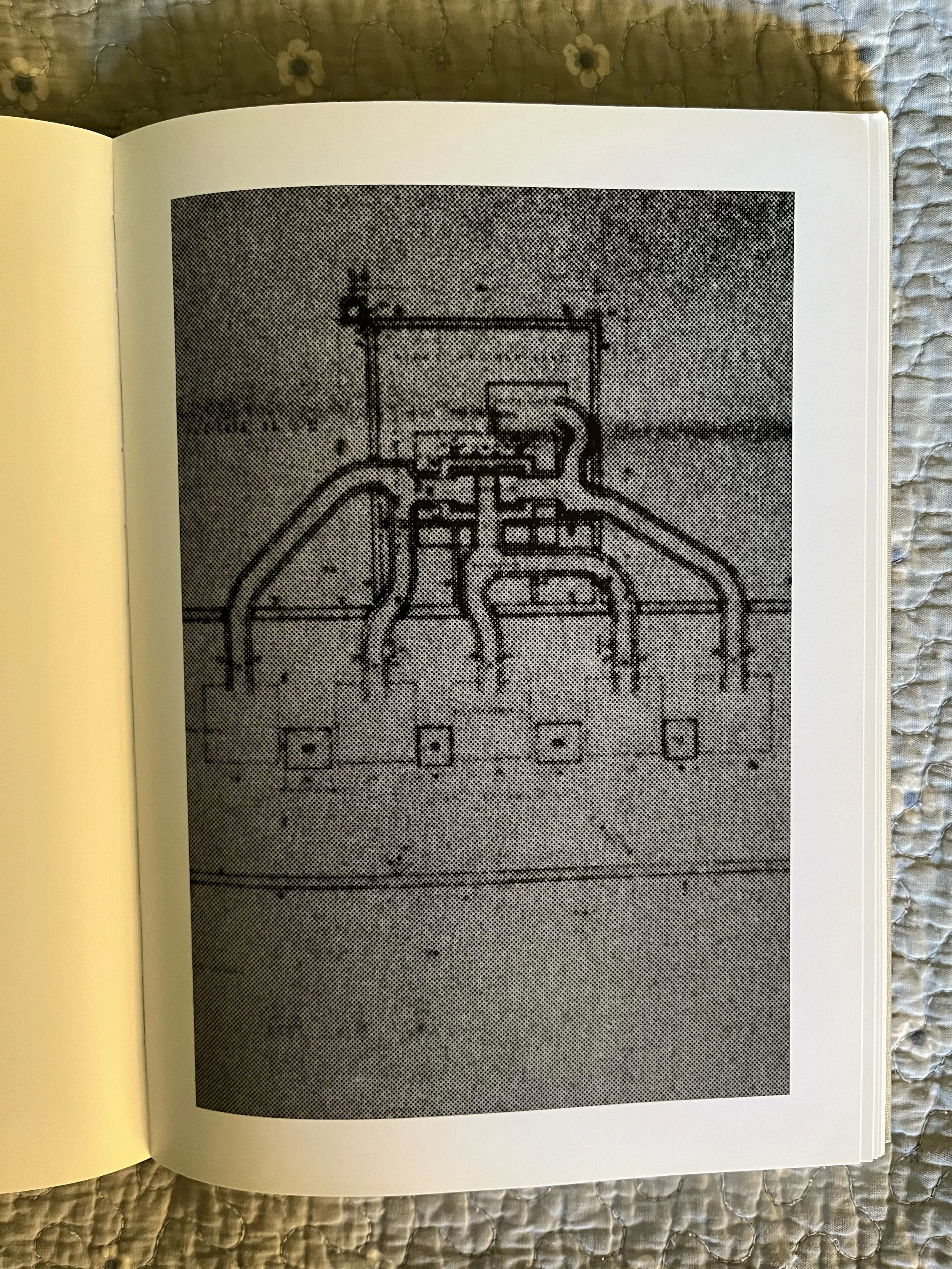

The fourth photograph in Ein-Heit.

The fourth picture is an extremely tight enlargement of a photo of what looks to me like the schematic of a concentration camp. I may have read somewhere that it is. Or perhaps the curator Thomas Weski told us that in a talk in the Hartford program. I don’t believe Mr. Schmidt talked about this photo when my cohort met with him. The fifth photo is an enlargement from a printed document of a man in a suit and hat, looking vaguely official and sinister. Now the reader is being somewhat alerted to what’s coming. The sixth photo is a detail from an embroidery depicting a lute player and another man doffing his hat, both in “period” clothing—the period being vaguely 17th to 19th century to my untutored eyes. It is clearly an image of nostalgia related to a happier, carefree time. (Always dangerous.)

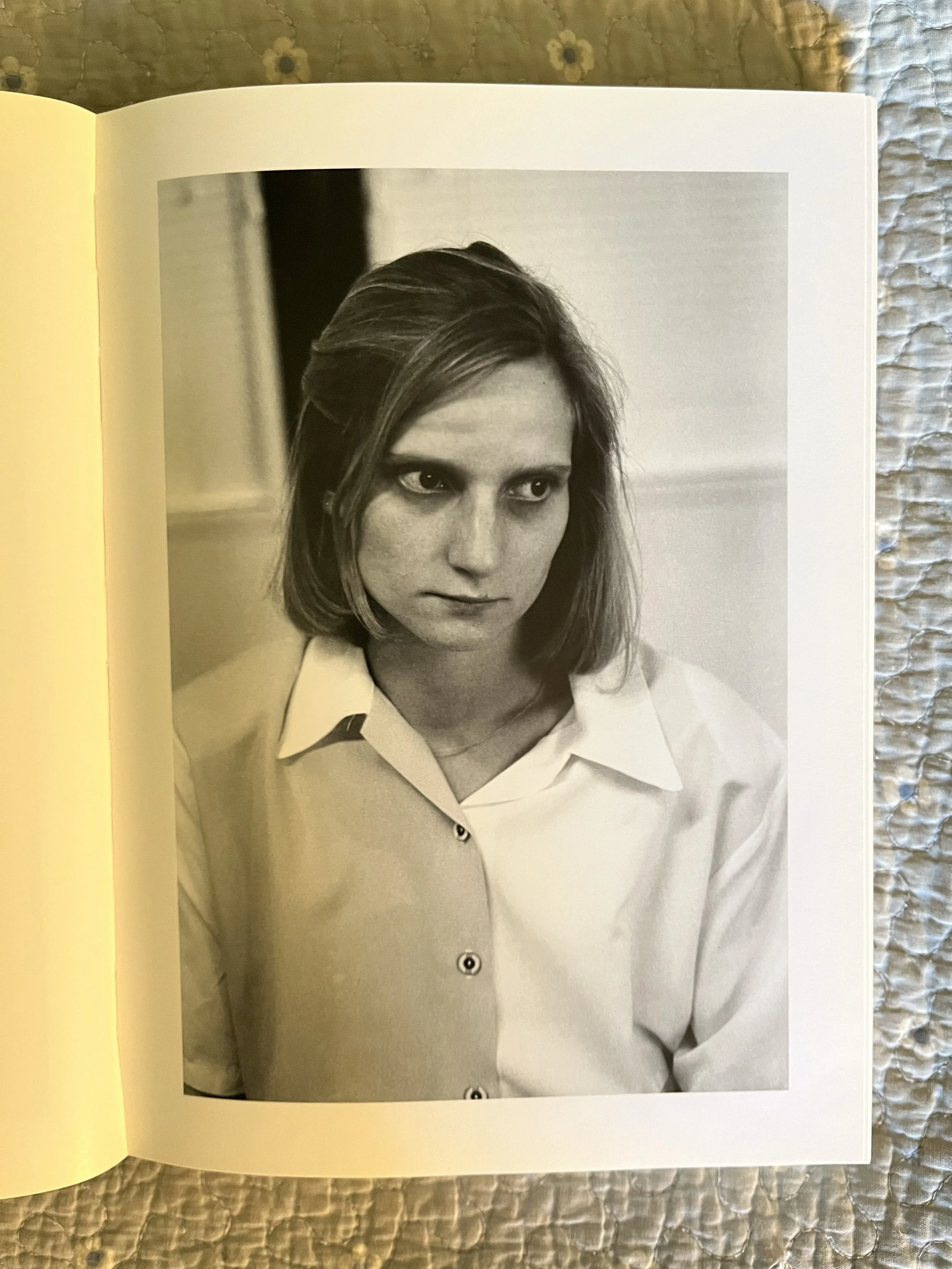

The fifth photograph in Ein-Heit.

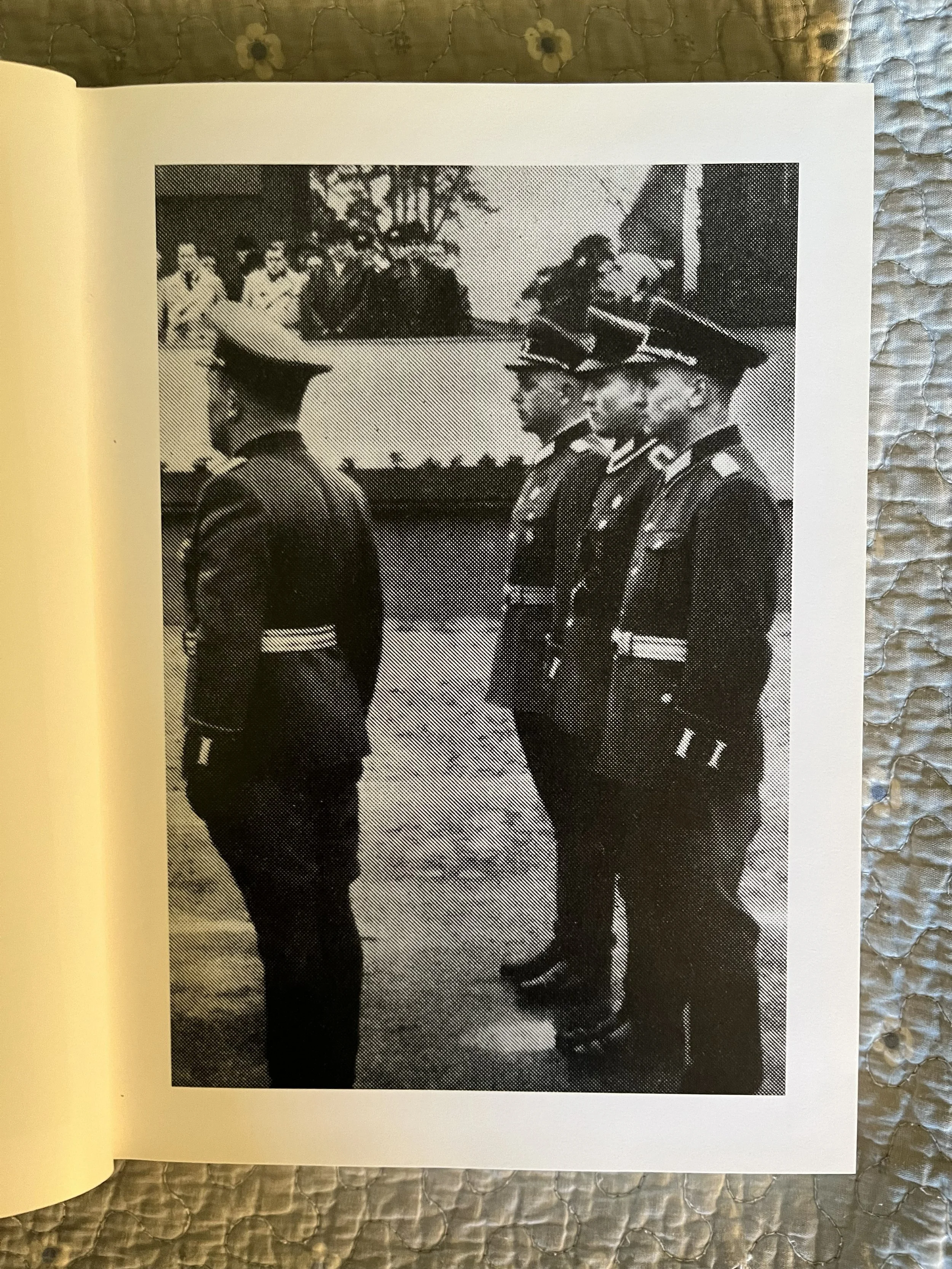

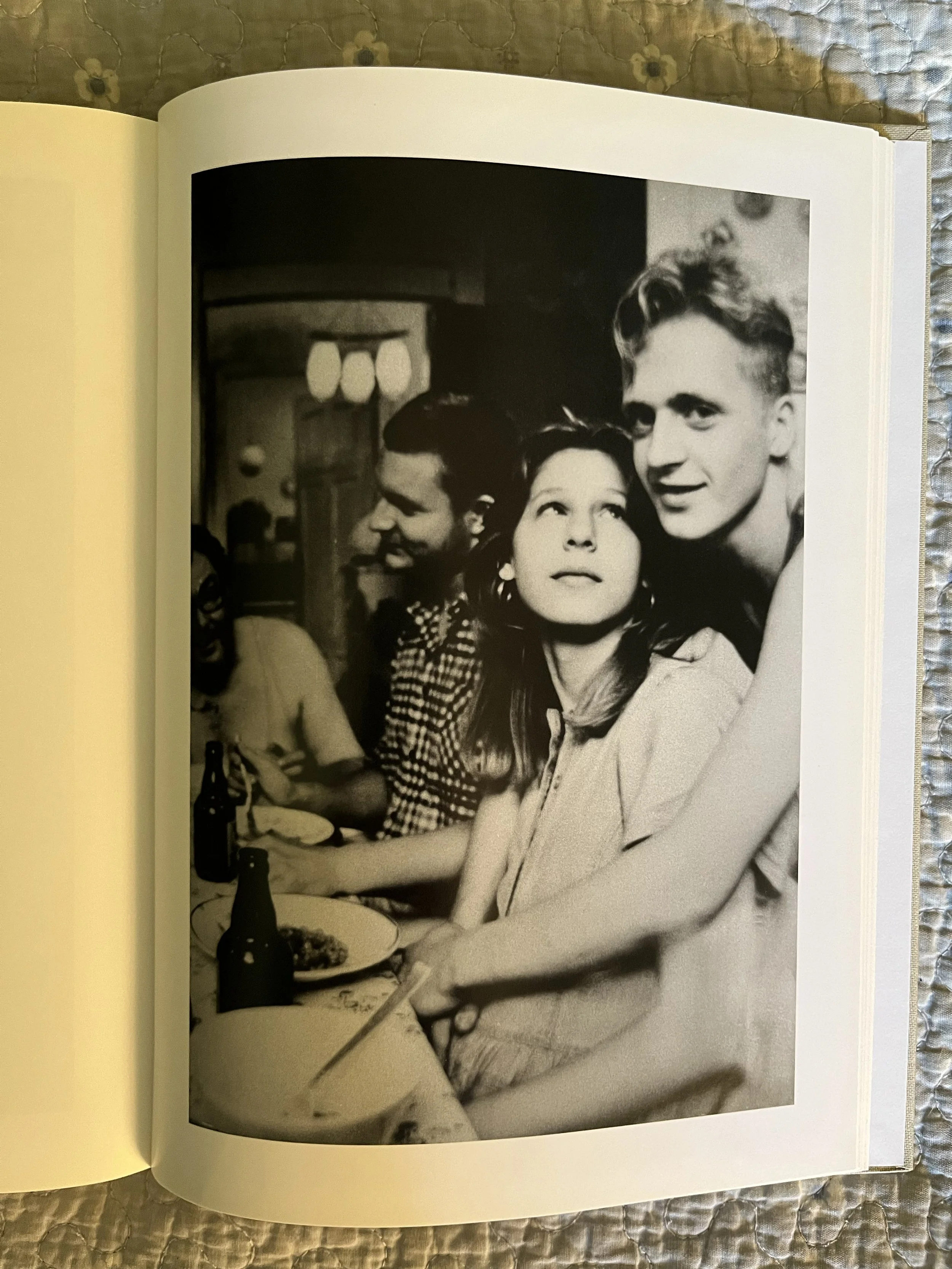

The seventh image is an appropriated photo of capped and uniformed soldiers standing at review, possibly Soviet-era DDR military, maybe BDG, but not overtly Nazis. That will come later. The book will continue to rhythmically show us historical images from different eras and Mr. Schmidt’s own photographs of buildings and portraits of more contemporary people, some looking official, some looking like civilians, including punkish youth. We are left to decide in each case which side of the German divide they represent, who or what they might be, and from what time period.

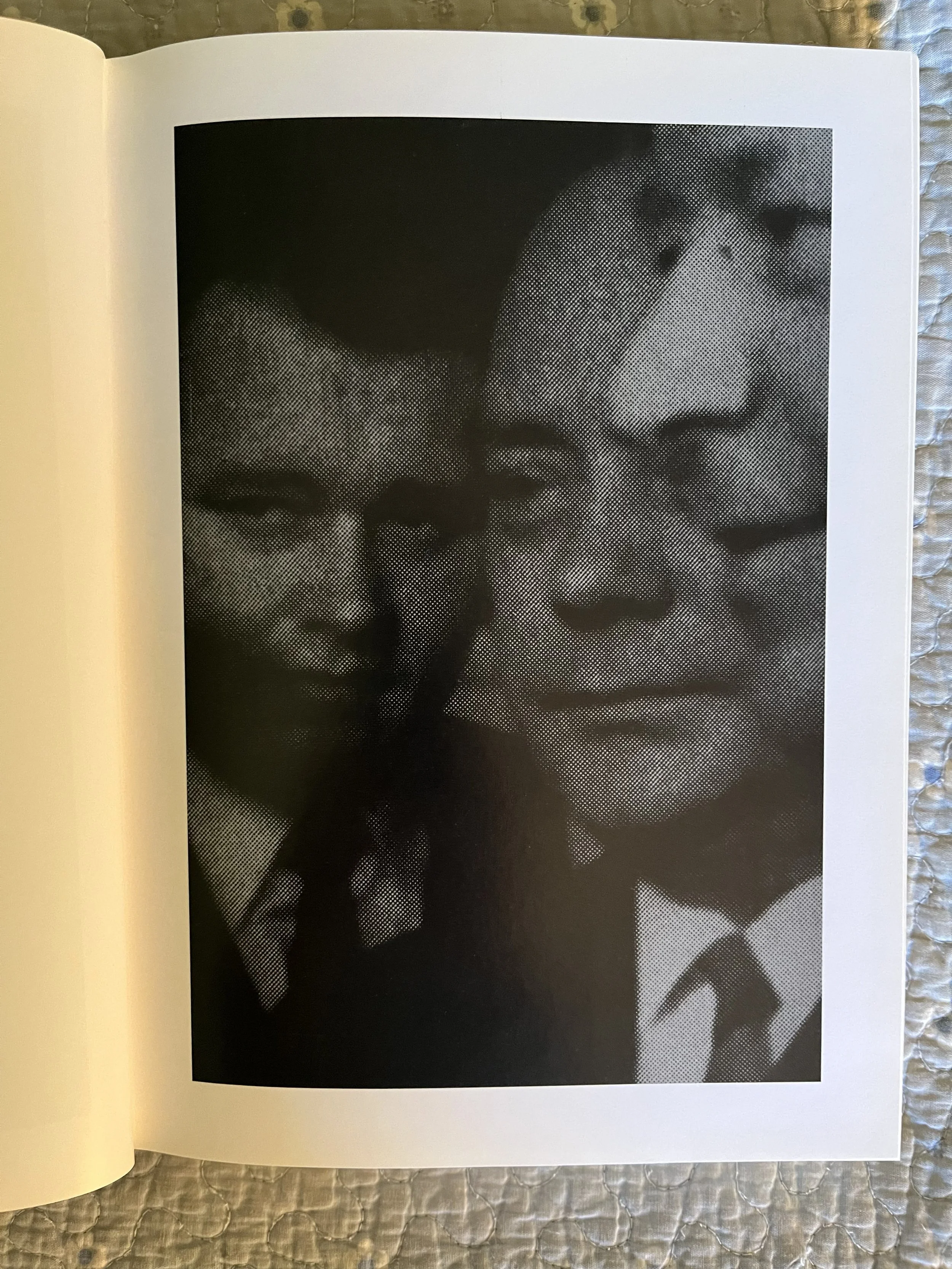

The seventh photograph in Ein-Heit.

Do you see what a failure it is to try to describe this book to you? But that’s OK, it’s all in the hope that you’ve either seen the book and will remember it, or you will soon see it. The book runs 314 pages, with most photographs on the right-hand page. Every time I pick up Ein-Heit, I watch myself turn from the first page to the last without stopping. It is, for me, that compelling.

Why? Why is this such a great book, in my estimation? First, because I’ve never experienced anything like it. Burning curiosity and uncertainty seem to merge with emotional responses to nearly every photograph. It’s as if Mr. Schmidt is plunging us into a mystery that is our mystery, whether we’re German or not. After all, the division and then the reuniting of Germany has had a deep impact on all our lives. Secondly, and I think this is crucial, I never feel the book is propagandistic or polemical. He’s not judging, he’s presenting. I cannot tell you from looking at the book how Mr. Schmidt feels about reunification, except that it’s big and important and historical.

I happen to be re-reading, for one of my own works, the slim little book War and the Iliad, which contains two main essays: one by Simone Weil, called “The Iliad, or the Poem of Force” (1939) and the other by Rachel Bespaloff, called “On the Iliad” (between 1939 and 1942). Both women were Jewish refugees from Hitler’s Germany, and Ms. Bespaloff’s essay is a response to Ms Weil’s essay. Ms. Bespaloff is comparing Homer and Tolstoy in her essay when she comments on the nature of the epic:

The style of the epic, when it attains the grandeur it has in Homer and Tolstoy, demands an accurate perception of true facts as well as the inclusiveness of an all-embracing view; it has no place for the arbitrary. It must give the sense of slowness and at the same time have the gift of brevity; it must have insights into collective states of mind and also into individual souls; it must capture the cosmic vision and be captivated by the anthropomorphic imagination; any partiality of judgment or sensibility is therefore impossible to it.

I had been wanting to write about the range of Mr. Schmidt’s photobooks, but reading this passage made me decide I had to write about just Ein-Heit alone, immediately. This passage describes part of why I’ve been so compelled by Ein-Heit for the 13 years I’ve owned a copy. It has grandeur. It has an all-embracing view of the breaking and rejoining of Germany and its shared history. It certainly has slowness, and yet enough brevity that, even at 314 pages, I always turn my way completely through it. And as I said, it’s not judging, it’s giving us an experience that is dark and sinister at times, but it’s an equal-opportunity darkness.

Meanwhile the portraits by Mr. Schmidt are profoundly compassionate and matter of fact and inclusive, although his sympathies clearly lie with the young Germans.

Most of all, I feel from this book a depiction of humanity, much as I do from Homer’s Iliad, with all the tragedy and some of the light which humanity entails. Images of power, force, youth, violence, love, betrayal, horror, and the drudgery of life are amassed and presented as a shared heritage of the German people who, at that time, were coming together again like a long-divorced couple hesitantly trying to give it one more go. People with no real idea what they were getting themselves into, and perhaps no clear memory of what had happened before. It seems that Mr. Schmidt was trying to remind them and keep them honest.

It’s possible to say that this is a depiction of the German soul, but somehow that doesn’t feel sufficient. It’s too easy a summation. It’s reductive, and this book is anything but reductive. The book is more like a step-by-step reconstitution of a memory, one that impresses, as happens in the Iliad, the actual feelings, the experiences, which constitute this memory. Each image closes a circuit in the brain and restores the force of each memory as an actual neural event, which is something words have a hard time doing. Because we can chose to hear or process words—or not. But an image cannot be evaded the same way. The retina sends the message immediately and directly to the brain.

The photographs don’t just reactivate memories, they also create images in the present moment, especially with the faces of people who are living this reunification at the time the images were made. Even though the Iliad was presenting events that happened in 1200 BC and was recorded in the poem around 800 BC, when Homer describes a lance penetrating near a soldier’s belly button and coming out the other side with bits of soldier attached, we viscerally experience that image in the immediate now. So, too, with the images in Ein-Heit. We experience them in the present, whether it’s a schematic of a gas chamber or the portrait of a young Berliner, even if we weren’t alive when the images were made.

Perhaps this is a large part of the power of Ein-Heit—that it is always the present. Distance of time, and even of place, have been erased. Even reading it again and again, I can’t remember what comes next when I turn the page. The force of its non-narrative structure helps assure, for me, its inexhaustible nature. So, too, the uncomfortable beauty of Mr. Schmidt’s photographs. Who can say if, fifty years from now, when everything in it will have been from so long ago, that this will still hold true for new viewers of the book. It’s impossible to know. I won’t be alive to see so you’ll have to tell me.

For insights into the artist, I highly recommend you read Jörg Colberg’s excellent blog post about Mr. Schmidt: https://cphmag.com/michael-schmidt