I listened yesterday to a Nearest Truth podcast in which Brad Feurhelm interviewed my friend from the Hartford MFA program Felipe Russo. Among other things, they discussed the beauty of the shorter photobook. They were talking about Felipe’s book Garagem Automática, which consists of 22 photographs.

I commented to Felipe on Instagram that this book felt to me infinite, but that I realized it’s because the images resonated infinitely for me, despite there being such a surprisingly small number of them. It’s a book that took four years to come about, I think he said, and I bet it could have included so many more images. But Felipe realized that 22 were enough.

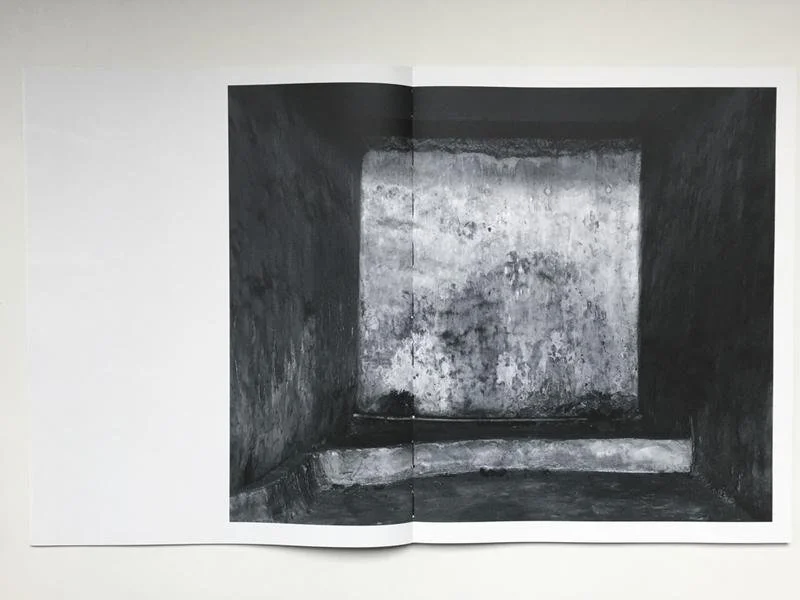

Spread from Felipe Russo, Garagem Automática.

I have witnessed the development of multiple photobooks from their naissance to their eventual publication, and I’ve seen a few cases involving a shift from what were tight, powerful edits to something larger. It struck me that the expansion of the work did not necessarily make it stronger. Rather, I wondered if the photobook publishers, and maybe the artists, grew the number of images to fill out an idea of what a serious photobook should be, which is: a large hardcover with between 60 and 80 photographs and well over 100 pages.

My sense is that the initial thread of an idea, or concept, can get lost as the number of images grow, and even the relations between the images can become more tenuous. This might have to do with memory’s capacity to hold onto images and relate them to each other. Or it might be that only so many images can be combined around one concept before either repetition or straying sets in.

Don’t get me wrong. I love images that don’t belong, or that surprise the reader––the hard left turn. But I have a suspicion that photographs sometimes end up included in a book both because of the general feeling that bigger is better, and because they’re really good photographs which the publishers and artists don’t want to leave out. The net result might be a collection of really good photographs that don’t necessarily deliver a unified experience. I think this connects to a revelation I had writing poetry in undergraduate school that once I started taking out words and lines the poems often got stronger.

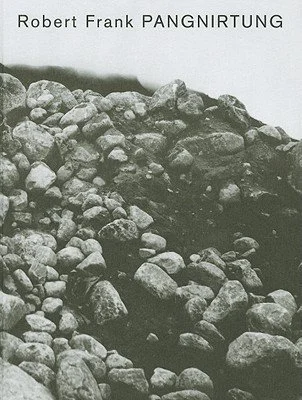

My favorite Robert Frank book—OK, yes, after The Americans—is Pangnirtung, which only has 27 photographs. I think I read once that he shot the images in a single week while visiting an Arctic village. It has a wholeness and a completeness that inspire me to try to make the same. And while it is a hardcover and is bigger in format, it’s a terribly slim book in the hand. The length allows for multiple “readings” in one sitting, which, for me, leads to a deeper contemplation of the book and its images.

The photographer Uta Genilke in Hamburg has been issuing a series of short, slim books, each serving a different theme or idea, and each of which feels like a full and complete piece. She prints these in small editions and they’re quite affordable. They also allow me to really feel the artist’s thinking through images and sequencing. Doing several shorter books I think also gives her a chance to address more ideas than trying to fit more photos under one title.

Uta Genilke. Sacre.

My personal favorite book by Bryan Schutmaat is Good Goddamn, which has 27 photographs made during a going-away celebration between two friends, one of whom was about to head to prison. (It wasn’t Bryan.) The work feels terribly personal and the emotions lift off the pages like mist. I believe Bryan said somewhere that it’s more of a zine, which I disagree with. It’s a book. It’s just a slim book. But to me it’s equally as important as his other longer books. (Brad Feurhelm and Felipe Russo mention that they believe a slim book is not automatically a zine.)

Bryan Schutmaat. Good Goddamn.

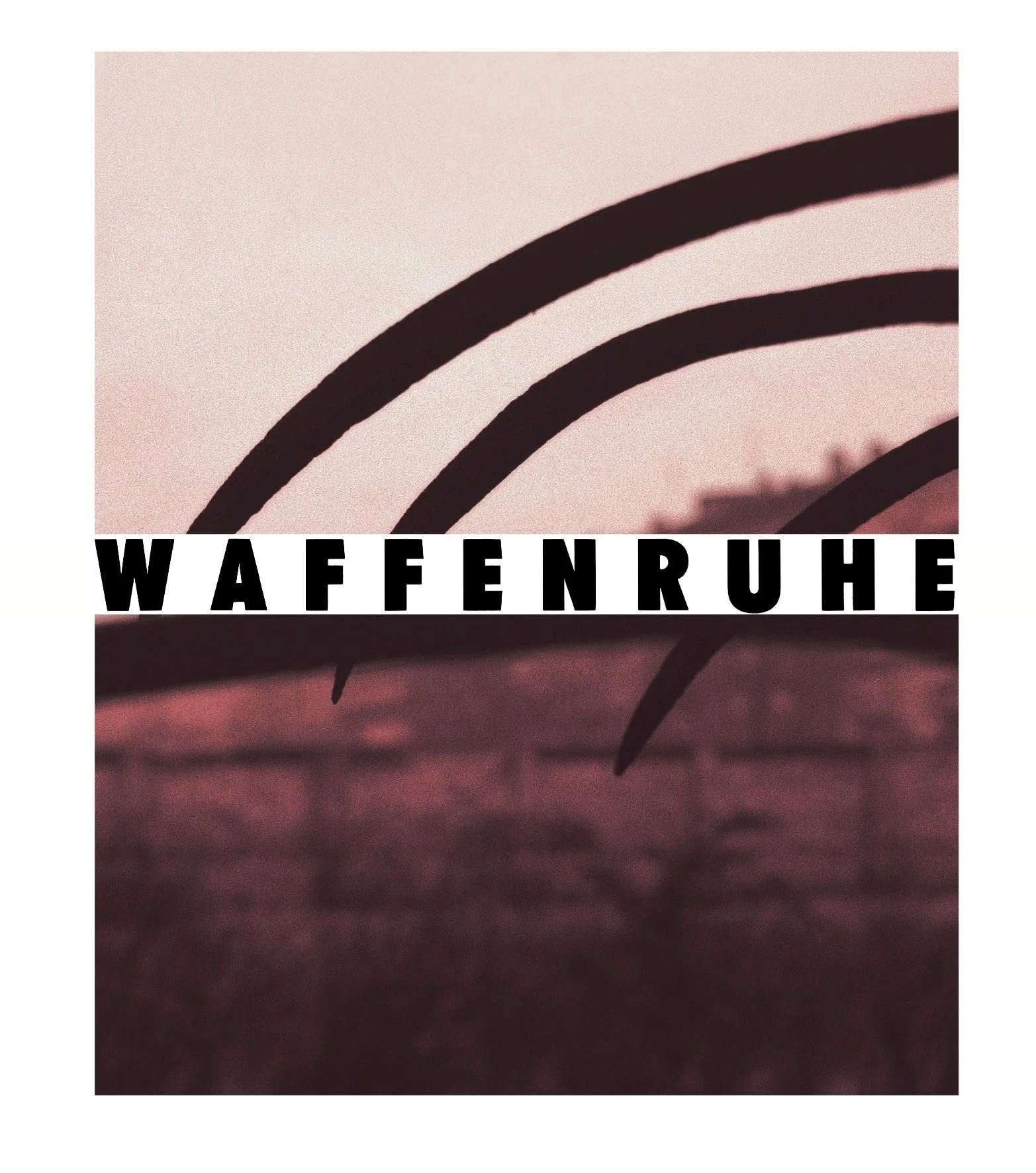

And while I love Michael Schmidt’s epic cloth-bound tome Lebensmittel, which clocks in at 264 pages, I find myself more frequently looking at Waffenruhe, a paperback which has 38 photos. I can’t imagine anything is missing at that length, and not a single image in the book feels superfluous.

I might also contrast Waffenruhe with John Gossage’s Berlin in the Time of the Wall, a monumental 464 page book, which I looked at very carefully and completely. Once. I haven’t taken it down from the shelf since. There are many extraordinary photographs in that book, but it’s an ordeal just to turn through the pages

Michael Schmidt. Waffenruhe.

Not that longer photobooks necessarily have superfluous images, but I suppose I’m saying that for me slim books often have more impact and hold me in the images, the idea, and the mind of the photographer longer. Yet I think many in the photobook world still see the big important hardcover as the highest accomplishment. I applaud the photographers who are gravitating toward shorter books that don’t make a grand statement but often speak more forcefully and more compellingly than their lengthier brethren.