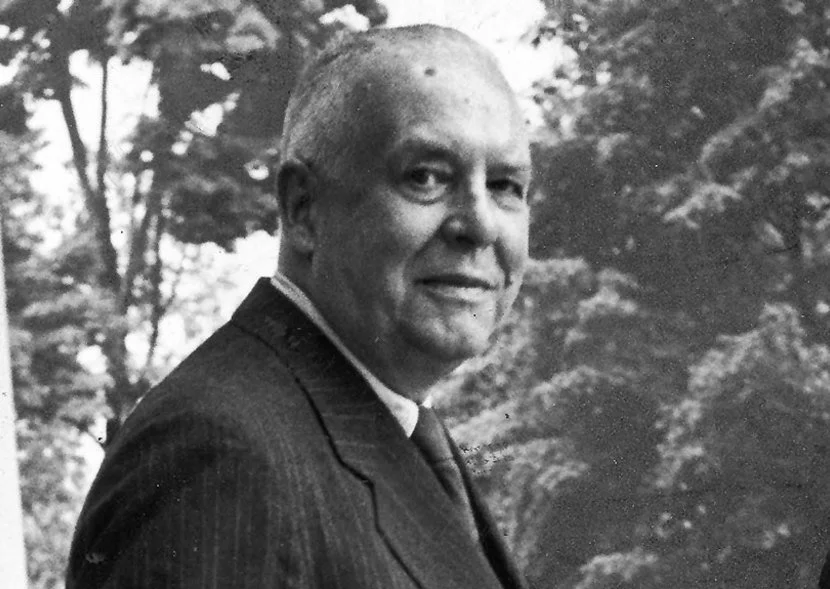

Two of the 20th century’s greatest poets had very traditional careers and wrote in their spare time. One was William Carlos Williams, who delivered over 3,000 babies in the Rutherford, New Jersey area as a doctor. The other was an attorney who rose through the ranks to become a vice-president at the Hartford Accident & Indemnity Company: Wallace Stevens.

Despite his conservative lifestyle in Hartford, he created in the mid-20th century some of the most innovative poetry ever written, even by today’s standards. I’m thinking in particular of his later poems, from 1950 onwards, which are deeply admired by the “experimental” poet Susan Howe. And appropriately so. They bear reading and rereading for their rich language, intellectual delicacy, and compelling ambiguities. Here’s the opening stanza from “To an Old Philosopher in Rome.”

On the threshold of heaven, the figures in the street

Become the figures of heaven, the majestic movement

Of men growing small in the distance of space,

Singing, with smaller and smaller sound,

Unintelligible absolution, and an end–

In contrast, Steven’s earlier poetry, particularly his famous book Harmonium (1923), is a lush, overgrown jungle of language at times, with great musicality and striking imagery. For instance, these opening lines from the poem “The Bird with the Coppery, Keen Claws:”

Above the forest of the parakeets,

A parakeet of parakeets prevails,

A pip of life among a mort of tails.

You will also notice, as you read him, that Stevens has the best poem titles of any poet you’ll find. In fact, he often began his poems by coming up with a title first, and then finding where it took him. (I have been doing the same with my photographic works, without knowing this was Steven’s approach.)

The most quoted poem of Stevens’ has to be “The Snow Man,” of which the final stanza reads:

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.”

There is one photographer, at least, who has paid great attention to Wallace Stevens, and that is Tim Carpenter in his book-length essay, To Photograph is to Learn How to Die. Carpenter sees Stevens as a materialist, but I see him in a slightly different light. I think it’s interesting to note that he converted to Catholicism on his death bed.

However his spirituality might be measured, Stevens could inspire a great amount of photographic work if he lands on your bookshelf. Fortunately for all of us, all his poetry and prose is to be found in one convenient book: Wallace Stevens: Collected Poetry and Prose, published by The Library of America (1997).

You can learn more about Stevens, and read several of his poems, at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/wallace-stevens.