I have never forgotten renting the short film called Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe back in the 80s. It was directed by Les Blank, who asked if he could film while Herzog fulfilled a promise he’d made to Errol Morris. Morris was a grad student and was complaining to the director about the difficulties of making his documentary Gates of Heaven. To push him along, Herzog vowed that if Morris completed the film Herzog would eat his shoe. Eventually the film was finished, Morris’s career as a director was born, and Herzog found himself one evening at the famous restaurant Chez Panisse in Berkeley.

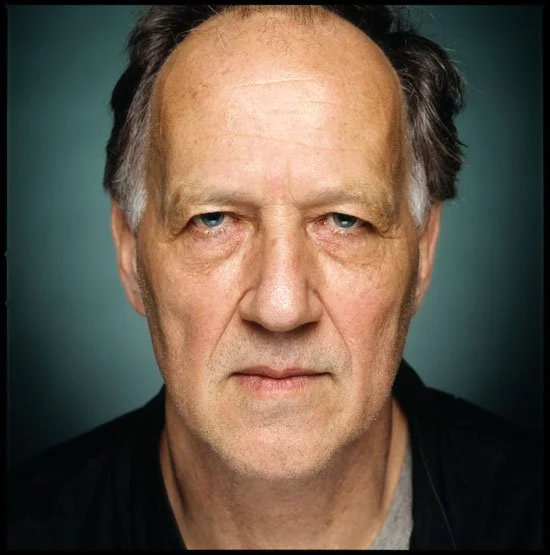

Werner Herzog. Photo by Robin Holland.

Chef Alice Waters had cooked the Clark Desert Boots—the shoes Herzog was wearing when he made the vow—in a garlic and herb-infused duck broth for five hours, While Blank rolled camera, Herzog sat in front of an audience with a tin snips and a Heineken and talked about art as he slowly consumed his shoe.

Alice Waters. Photo by Platon.

Watching the film way back then was like drilling holes in my skull and standing in a torrential downpour. My head was filled with Herzog’s words. I will quote one of the most important statements I’ve ever heard about visual arts:

Give us adequate images. We, we lack adequate images, our civilization doesn't have adequate images. And I think our civilization is doomed, is gonna die out like dinosaurs if it does not develop an adequate language or adequate images.

This is one of the two ever-persistent koans that I’ve meditated on throughout my photographic practice. The other was a directive from Robert Lyons, the head of the Hartford Art School MFA I attended, who said to me, in the face of my intellectualizing: “There are different kinds of intelligence. There’s a retinal intelligence.”

Robert Lyons.

Back to Herzog. Over and over I pondered the question, What is an adequate image? I accepted Herzog’s assertion whole-heartedly. I just didn’t really know what it meant. Years later I found out that Garry Winnogrand was also deeply impacted by Herzog’s statement. Yet clearly Winnogrand and everyone else who has struggled with this conundrum has come up with different answers. And that’s probably exactly the point.

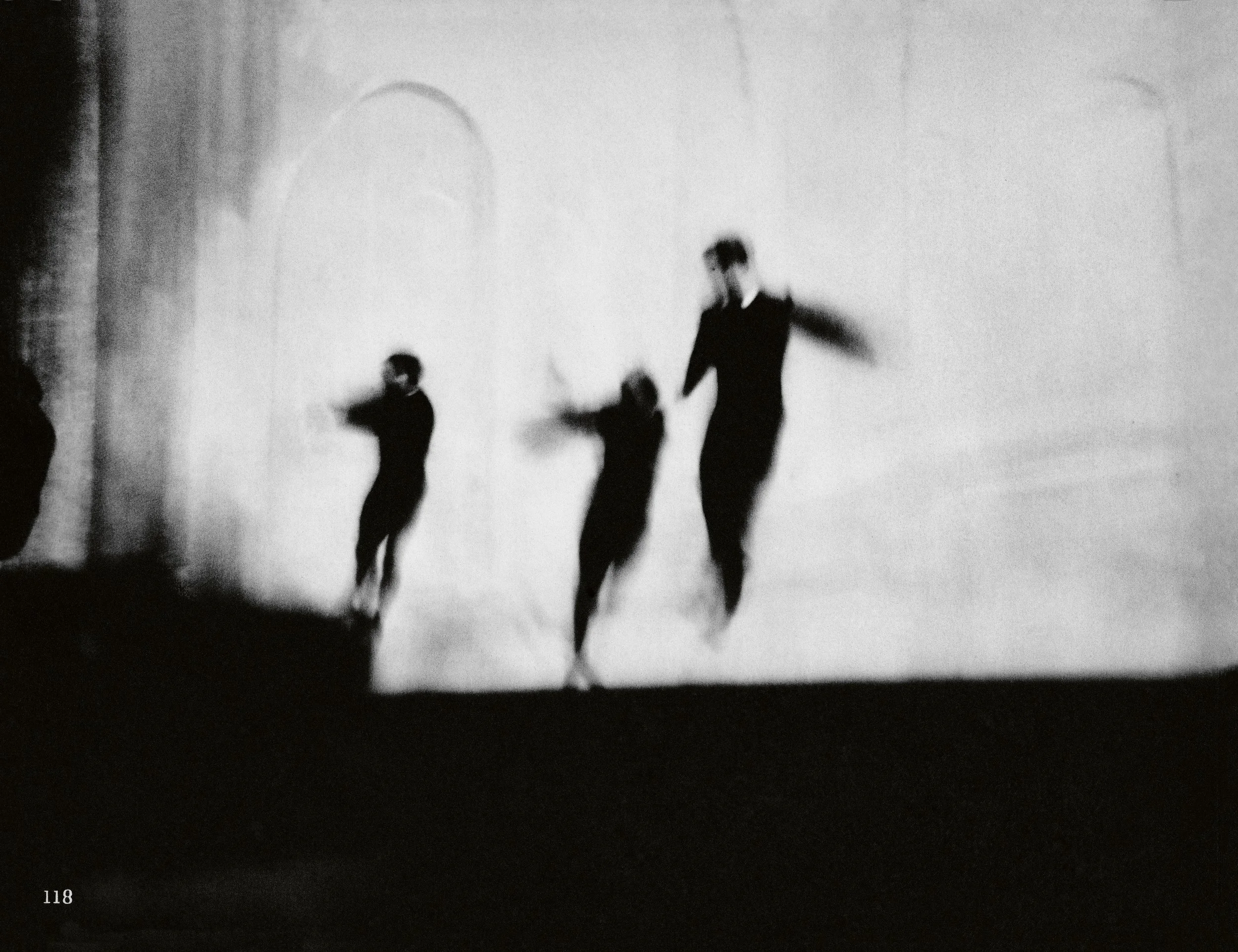

It strikes me that the definition of an “adequate image” quite likely changes by the decade, year, day, and hour. What was once adequate might not be adequate any longer. Conversely, there are many of what seem to me to be inadequate images made today while the photographs of Harry Callahan or Alexey Brodovitch feel entirely adequate sixty years later.

Photo by Harry Callahan.

So how do we know what’s adequate and what isn’t? I think, more than anything, there’s a feeling that is often nearly instantaneous that signals the answer. Perhaps this goes back to Robert Lyon’s term “retinal intelligence.” A study by MIT neuroscientists determined that the brain can process entire images in as little as 13 milliseconds. It turns out the retina is actually made of brain matter, and transmits visual information straight to our brain without any mediation.

I also suspect that each individual photographer exists to expand the number of eyes looking for adequate images on humankind’s behalf. Therefore, the number of photographers out there matters. Because some of us are going to get it right. And the definition of getting it right will constantly change over time.

From Ballet. Photo by Alexey Brodovitch.

I think that, subconsciously at least, we all know what an inadequate image feels like. To me it can feel any of the following ways: familiar, clichéd, safe, manipulative, simplistic, nostalgic, etc. Mark Steinmetz told our cohort at Hartford that “something needs to be at risk” in our photography.

Mark Steinmetz. Photo by Andre Wagner.

Perhaps this is all part of what makes art hard for artists. Its never a question that gets answered, there’s never a sense of landing on the proper way of making an adequate image. Instead, it keeps us off-balance, anxious, uncertain, questioning, and rather desperately hunting. We never get to coast. But I do personally feel, like Herzog, that much is at stake.